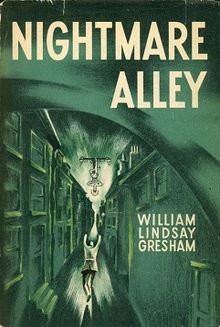

NIGHTMARE ALLEY by the late William Lindsay Gresham (1909-1962) is one of the bleakest, most relentless American novels of all time. Initially published in 1946, it was an immediate bestseller, and remains one of literature’s most enduring portrayals of the unflattering realities of carnival life and the dark side of the American Dream. It also functions as a powerful character study, with a narrative flow that ranges from starkly naturalistic to overtly hallucinatory.

NIGHTMARE ALLEY by the late William Lindsay Gresham (1909-1962) is one of the bleakest, most relentless American novels of all time. Initially published in 1946, it was an immediate bestseller, and remains one of literature’s most enduring portrayals of the unflattering realities of carnival life and the dark side of the American Dream. It also functions as a powerful character study, with a narrative flow that ranges from starkly naturalistic to overtly hallucinatory.

…it was an immediate bestseller, and remains one of literature’s most enduring portrayals of the unflattering realities of carnival life and the dark side of the American Dream.

Disarmingly simple in conception, it pivots on Stanton Carlisle, an ambitious young man who joins a traveling carnival. It’s there that he develops a fascination for the geek—i.e. a disgraced drunk who bites the heads off chickens for the edification of ravenous mobs. Gresham, incidentally, claimed it was NIGHTMARE ALLEY that introduced the term geek into common language.

After inadvertently causing the death of one of his shyster mentors (you can be sure there are more deaths to come) and convincing a nosy cop that a relative is contacting him from beyond the grave, Stan discovers his calling: he becomes a spiritualist. As such he bilks rich folk out of obscene amounts of money for the privilege of contacting their deceased relatives or clearing out the spirits haunting their houses. Aided by the appropriately monikered Lilith, a psychiatrist with amoral designs of her own, Stan goes to great lengths to perpetuate his spiritualist ruse, including breaking into a client’s house to stage a haunting and hiring a dwarf to impersonate a dead child.

Gresham, incidentally, claimed it was NIGHTMARE ALLEY that introduced the term geek into common language.

That Stan is eventually done in by this charade is hardly a surprise given all the foreshadowing the author provides, from an early dissertation on circus geeks (more on this below) to the frequent nightmares Stan experiences involving the titular alley. Further macabre foreshadowing is provided by the chapter headings, which are named after tarot cards, and come complete with symbolic definitions (such as “Resurrection of the Dead,” defined thusly: “By the call of an angel with fiery wings, graves open, coffins burst, and the dead are naked“).

Stan’s minutely described spiral into alcoholism and homelessness is an agonizingly prolonged one, with a final humiliation that can be viewed as either the ultimate nihilistic flourish or an act of bloody redemption. The latter view was adopted by, among others, the notorious graphic artist Joe Coleman, who performs his own brand of circus geekdom by biting the heads off live rats, apparently in tribute to the concluding passages of NIGHTMARE ALLEY.

Gresham, for his part, was never able to reca pture the power of his debut novel. It certainly has a fire and energy redolent of a one-off, suggesting its creator shot his proverbial load in its creation-–of which Gresham later claimed that “twenty years of research went into the book, plus two years of plotting and eight months of actual writing.”

pture the power of his debut novel. It certainly has a fire and energy redolent of a one-off, suggesting its creator shot his proverbial load in its creation-–of which Gresham later claimed that “twenty years of research went into the book, plus two years of plotting and eight months of actual writing.”

A second novel entitled LIMBO TOWER appeared in 1949; set in a hospital ward rampant with disease and death, it failed to achieve, or even approach, the impact of its predecessor. Subsequent Gresham books included a 1959 biography of Harry Houdini and MONSTER MIDWAY, a 1953 collection of articles about carny life. He also published numerous short stories that were collected in the 2013 volume GRINDSHOW, which also contains a lengthy biographical essay on Gresham by filmmaker Bret Wood.

The latter is an especially revealing document, showing just how closely Gresham’s life mirrored that of Stanton Carlisle. Alcoholism was a constant in both, as were spousal abuse and mental problems. Gresham’s end, unfortunately, was as fraught as that of this antihero: he committed suicide in 1962 after being diagnosed with cancer of the tongue.

The death of William Lindsay Gresham was little noticed by the world at large, but NIGHTMARE ALLEY has lived on in various incarnations. In fact, according to Fantagraphics editor Gary Groth, “more artists have worked on NIGHTMARE ALLEY, adapting it into more media, than just about any other piece of fiction.”

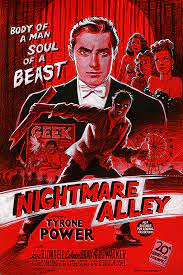

The most recent of those adaptations was Guillermo Del Toro’s 2021 film, which was heavily inspired by the 1947 Edmund Goulding directed NIGHTMARE ALLEY. The latter is an almost-great transposition of Gresham’s masterpiece, marred only by a thoroughly misconceived ending. A shame, really, as it’s a handsomely mounted piece of noir filmmaking, with the matinee idol Tyrone Power ditching his heartthrob image in favor of a full-bodied incarnation of Stanton Carlisle.

… among the absolute “noirest” of the film noirs—that seems uniquely suited to the material. The sound design is equally impressive in its way, with the wail of a circus geek recurring on the soundtrack during opportune moments.

Power reportedly demanded that the novel’s bleakness be preserved, and Gresham’s fatalistic tone is indeed perfectly replicated, down to the tarot cards that eerily prefigure Powers’ downfall. That’s despite the fact that the narrative doesn’t always follow that of the novel, with the private séances so pivotal to the text ditched in favor of a succession of nightclub performances. Another deviation from the novel deviation is the film’s distractingly preachy angle, exemplified by a lengthy scold by Power’s girlfriend (the recently deceased film noir mainstay Colleen Gray) about how he’s “going against God.”

The film, photographed by the great Jules Furthman, is marked by superbly stark and shadowy black and white imagery—it’s among the absolute “noirest” of the film noirs—that seems uniquely suited to the material. The sound design is equally impressive in its way, with the wail of a circus geek recurring on the soundtrack during opportune moments.

But again, there’s that horrendous ending, which attempts to add a note of tacked-on optimism to this most caustic of tales. Ordered, apparently, by Twentieth Century Fox head Darryl Zanuck, NIGHTMARE ALLEY’S concluding moments—topped off by the observation “How can a guy get so low? He reached too high”—are a serious annoyance. Tyrone Power deserves credit for his efforts at conserving the novel’s dark edge, but his clout evidently didn’t stretch very far.

“How can a guy get so low? He reached too high.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, NIGHTMARE ALLEY was a box office flop, and Tyrone Power returned to the type of swashbuckling pap with which he made his name. Furthermore, NIGHTMARE ALLEY was “lost” for decades due to a dispute between its producer George Jessel and the William Lindsay Gresham estate, with the 2005 20th Century Fox DVD release being its premiere home video appearance in the US.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, NIGHTMARE ALLEY was a box office flop, and Tyrone Power returned to the type of swashbuckling pap with which he made his name. Furthermore, NIGHTMARE ALLEY was “lost” for decades due to a dispute between its producer George Jessel and the William Lindsay Gresham estate, with the 2005 20th Century Fox DVD release being its premiere home video appearance in the US.

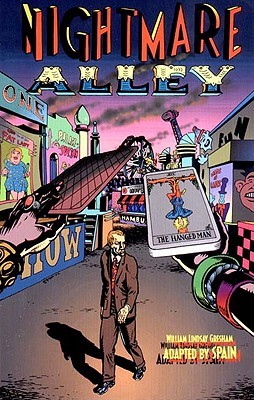

In 2003 a graphic novel adaptation of NIGHTMARE ALLEY, written and illustrated by Spain (a.k.a. Spain Rodriguez), was published by Fantagraphics Books. Rendered, appropriately, in ultra-stark black and white, Spain’s work on NIGHTMARE ALLEY has a lurid, trashy air that ideally fits the material. Spain possesses an eye for ugliness and sleaze, and pays close attention to background action in his panels, which depict an amoral world of whores and hucksters in which Stanton’s trickery doesn’t seem especially out of place.

My only problems with Spain’s NIGHTMARE ALLEY are the overly voluminous dialogue balloons, which are among the wordiest of any comic or graphic novel, and take up a great deal of page space. That’s a minor complaint, however, in an otherwise uniformly impressive piece of work.

A more recent NIGHTMARE ALLEY incarnation is also its most unexpected: a stage musical. Scripted by Jonathan Brielle, the NIGHTMARE ALLEY musical was performed in mid-2010 at Los Angeles’ Geffen Playhouse, under the direction of filmmaker Gilbert Cates and headlined by James Barbour. I haven’t seen the show, but the reviews weren’t exactly encouraging; according to a Los Angeles Times critic, “When I go to a show called NIGHTMARE ALLEY, I expect at least one shiver up my spine. I’ve ordered coffee beverages at Starbucks more perverse than this show.” The book’s dark ending, at least, was apparently retained, for which Brielle and Cates deserve credit.

Regarding that ending, I feel duty-bound to transcribe its unforgettable final line, given that it is in many respects the most memorable portion of Gresham’s novel. (Here, obviously, I’ll insert a major SPOILER ALERT!!!) Said line echoes a claim made early in the text, when a carnival barker describes the science of geekdom to a young Stanton Carlisle: “You pick up a guy who ain’t a geek–he’s a drunk…(and) you tell him this: I got a little job for you…We got to get a new geek. So until we do you’ll put on the geek outfit and fake it.” Onto the final page, which features another barker chatting up a much older Stanton: “I got one job you might take a crack at…What do you say? Of course it’s only temporary—just until we get a real geek.”

See also Nightmare Alley (Film).