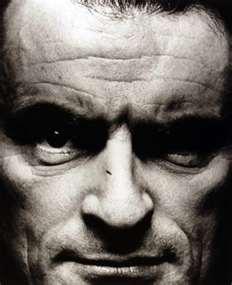

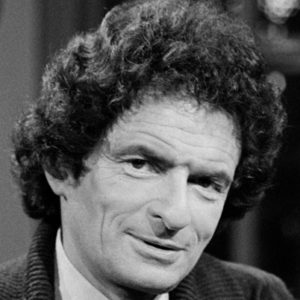

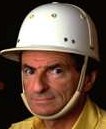

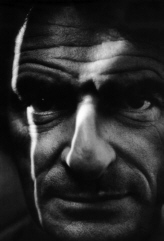

The late Jerzy Kosinski (1933-1991) remains a shadowy and enigmatic figure. A novelist of undeniable brilliance, Kosinski achieved a fair amount of fame in his time. These days it seems that most of Kosinski’s fiction has been largely forgotten–as, unfortunately, has James Park Sloan’s excellent 1996 biography on the man–but for 1965’s THE PAINTED BIRD, the novel that both made Kosinski’s reputation and destroyed it.

The late Jerzy Kosinski (1933-1991) remains a shadowy and enigmatic figure. A novelist of undeniable brilliance, Kosinski achieved a fair amount of fame in his time. These days it seems that most of Kosinski’s fiction has been largely forgotten–as, unfortunately, has James Park Sloan’s excellent 1996 biography on the man–but for 1965’s THE PAINTED BIRD, the novel that both made Kosinski’s reputation and destroyed it.

THE PAINTED BIRD is a profoundly disturbing journey through a living Hell, or at least the closest thing to it: Eastern Europe under Nazi rule. The focus is on a nameless dark haired boy wandering from one rural village to another after his Jewish parents abandon him. He witnesses countless bizarre, grotesque and surreal escapades, often finding himself under attack from vicious peasants, dogs and other kids. Around the halfway point the boy is flung into a manure pit by a hostile mob and loses his voice, which only makes things worse. He eventually turns to evil, which seems an unavoidable consequence of the preceding traumas, before unexpectedly regaining his voice in a skiing accident.

THE PAINTED BIRD is a profoundly disturbing journey through a living Hell, or at least the closest thing to it: Eastern Europe under Nazi rule. The focus is on a nameless dark haired boy wandering from one rural village to another after his Jewish parents abandon him. He witnesses countless bizarre, grotesque and surreal escapades, often finding himself under attack from vicious peasants, dogs and other kids. Around the halfway point the boy is flung into a manure pit by a hostile mob and loses his voice, which only makes things worse. He eventually turns to evil, which seems an unavoidable consequence of the preceding traumas, before unexpectedly regaining his voice in a skiing accident.

The novel has evoked a variety of reactions. It’s been dismissed as “the fantasies of a sick mind,” yet also praised by the likes of Arthur Miller, Luis Bunuel and Anais Nin, who claims that “by the great beauty of its style it lifts the entire experience to the philosophic, mythological realms of knowledge.” I agree.

Told in a simple and detached voice that takes into account both the natural and supernatural worlds, THE PAINTED BIRD provides one of fiction’s only truly convincing portrayals of a child’s worldview. Equally well delineated is the atmosphere of everyday depravity suffusing a war-torn environment, where ignorance and superstition hold sway.

Kosinski liked to claim THE PAINTED BIRD was a work of “Autofiction,” even going so far as to report events from it–the manure pit trauma among them–as fact in a lengthy self-penned author bio that appeared in paperback editions of his novels. To be fair, Kosinski did grow up in Poland during WWII, like the kid in THE PAINTED BIRD, and did apparently experience and/or witness a fair amount of abuse. Yet the facts (according to James Park Sloan, at least) are unequivocal: Kosinski was not separated from his parents, never lost his voice, and didn’t spend much time wandering the countryside, having lived in hiding with his family in the homes of several Poles. As elucidated by Sloan, Kosinski was taught from an early age to conceal his Jewishness, and essentially live a lie–a tendency Kosinski carried over into his adult life.

Another claim Kosinski made about THE PAINTED BIRD was that he’d drafted it in English despite the fact that at the time he was only semi-fluent in the language. In truth a variety of uncredited translators assisted in preparing the text (a practice Kosinski continued with the rest of his novels, although not as intensely as he did with THE PAINTED BIRD). This, it seems, was largely responsible for the book’s disarmingly measured and unemotional tone, which never loses its composure, even when detailing the most horrific acts.

Jerzy Kosinski’s following novel, 1968’s STEPS, was just as important in establishing the burgeoning Kosinski myth. The writing was stronger and more assured in this, Kosinski’s most overtly experimental text. It’s the highly fragmented account of a nameless first-person individual and his varied exploits, most of them extremely violent and sexual in nature. Said protagonist is closely patterned after Kosinski himself, having like Kosinski immigrated from Eastern Europe to the U.S. in his early twenties, and working, as Kosinski did, as a limo driver.

Jerzy Kosinski’s following novel, 1968’s STEPS, was just as important in establishing the burgeoning Kosinski myth. The writing was stronger and more assured in this, Kosinski’s most overtly experimental text. It’s the highly fragmented account of a nameless first-person individual and his varied exploits, most of them extremely violent and sexual in nature. Said protagonist is closely patterned after Kosinski himself, having like Kosinski immigrated from Eastern Europe to the U.S. in his early twenties, and working, as Kosinski did, as a limo driver.

Many of the remainder of Kosinski’s novels followed the basic outline of STEPS, being highly episodic, dispassionately told accounts of cagey European-bred men fucking and fighting their way through 1970s America. THE DEVIL TREE (1973), COCKPIT (1975), BLIND DATE (1977) and PASSION PLAY (1979) all followed this formula, being impeccably written, frequently shocking novels that suffer from over-familiarity and lack the enigmatic fascination of STEPS.

An element Kosinski utilized in these novels was one that went back to THE PAINTED BIRD: the inclusion of faux-autobiographical elements. In COCKPIT, for instance, the disaffected European protagonist obtains a U.S. visa by creating a fictional individual whose testimony on the protagonist’s behalf convinces Polish authorities to grant him release. This account is recited as fact in Kosinski’s aforementioned self-penned author bio, even though Kosinski actually utilized more conventional methods in emigrating to America. See also BLIND DATE, whose protagonist is at one point on his way to the Hollywood home of a moviemaker colleague, only to be waylaid when the airline loses his luggage in New York; in this way he narrowly misses out on a mass murder that takes place in his friend’s house. Once again the basis of this account was a “true” story Kosinski liked to relate about his longtime pal Roman Polanski and the 1969 murders of the latter’s wife and friends by followers of Charles Manson, which Kosinski claims he narrowly missed out on (a claim that has long been a subject of debate–in his autobiography Polanski says it’s false).

Further Kosinski novels include the oddly comedic BEING THERE (1971) and the music-centered mystery PINBALL (1982), both of which are in my view stronger than the auto-fiction quartet (though not Kosinski’s final book, 1988’s outrageously self-indulgent HERMIT OF 69TH STREET, which I find unreadable).

Further Kosinski novels include the oddly comedic BEING THERE (1971) and the music-centered mystery PINBALL (1982), both of which are in my view stronger than the auto-fiction quartet (though not Kosinski’s final book, 1988’s outrageously self-indulgent HERMIT OF 69TH STREET, which I find unreadable).

The beginning of the end, in any event, came in 1982, when the Village Voice published an article entitled “Jerzy Kosinski’s Tainted Words” that among other things exposed THE PAINTED BIRD as the entirely fictional work it is. By that point Kosinski had a formidable reputation not only as a skilled novelist but also a distinguished intellectual. The Village Voice article didn’t entirely demolish Kosinski’s reputation, but did it irreparable damage nonetheless, which appears to have led to a period of depression that culminated in Kosinski’s May 3, 1991 suicide at age 57. In the words of Mr. Sloan, “There was a hollow space at the center of Kosinski that had resulted from denying his past, and his whole life had become a race to fill in that hollow space before it caused him to implode, collapsing inward upon himself like a burnt-out star.”

That suicide made headlines, as I recall, not for Kosinski’s literary stature but for the singularly macabre way he did himself in: after taking a fatal dose of barbiturates he lay down in a warm bath and tied a plastic bag around his head. To readers of his novels, with their innumerable grotesqueries, the methodology of Kosinski’s suicide won’t seem entirely surprising.

That suicide made headlines, as I recall, not for Kosinski’s literary stature but for the singularly macabre way he did himself in: after taking a fatal dose of barbiturates he lay down in a warm bath and tied a plastic bag around his head. To readers of his novels, with their innumerable grotesqueries, the methodology of Kosinski’s suicide won’t seem entirely surprising.

A distinguished literary giant and fascinatingly complex individual he may have been, but Jerzy Kosinski was also a deeply troubled man with a penchant for torturing dogs and wandering dark streets at night–things fully in keeping with his disturbed imagination. I agree with the critic who dubbed him “one of our most distinguished writers,” but also tend to side with another who claimed, less admiringly, that “Kosinski makes my skin crawl.”