Today marks the 40th anniversary of the June 20, 1975 release of Steven Spielberg’s JAWS. Unless you’ve been living on the bottom of the ocean for the past four decades you’re probably aware that JAWS is one of the most iconic blockbusters of all time, and the one movie that more than any other is responsible for elevating the age-old monster movie model, once a staple of grade-B moviemaking, into the big budget arena. It’s a fact that quite a few elements of JAWS emerge directly from B-movie territory, including its most remarked-upon conceit: the fact that the great white shark that provides the film’s raison d’etre is kept largely off-screen, a staple of monster movies from time immemorial. Of course, the B-movies of old generally kept the monsters out of sight due to the fact that the critters didn’t always work, and apparently that was also the case with the more substantially budgeted JAWS.

Today marks the 40th anniversary of the June 20, 1975 release of Steven Spielberg’s JAWS. Unless you’ve been living on the bottom of the ocean for the past four decades you’re probably aware that JAWS is one of the most iconic blockbusters of all time, and the one movie that more than any other is responsible for elevating the age-old monster movie model, once a staple of grade-B moviemaking, into the big budget arena. It’s a fact that quite a few elements of JAWS emerge directly from B-movie territory, including its most remarked-upon conceit: the fact that the great white shark that provides the film’s raison d’etre is kept largely off-screen, a staple of monster movies from time immemorial. Of course, the B-movies of old generally kept the monsters out of sight due to the fact that the critters didn’t always work, and apparently that was also the case with the more substantially budgeted JAWS.

JAWS was also the first true summer blockbuster, creating a bigger-is-better distribution template that remains in effect today. Yes, there is a very evident through-line between JAWS and JURASSIC WORLD, especially since the latter is a sequel to 1993’s Steven Spielberg directed JURASSIC PARK, a movie that blatantly reworked the JAWS formula (which for that matter was itself a reworking of Spielberg’s earlier TV movie DUEL—Spielberg admittedly thought of JAWS as “DUEL on the water”).

Another much remarked-upon aspect of JAWS is its calamitous production. Due to the fact that so much of it was lensed on the open sea (always a dicey proposition, as the makers of WATERWORLD would discover twenty years later), the shoot was apparently a protracted nightmare for everyone involved.

The Film

Admittedly, JAWS hasn’t dated entirely well. Certain elements no longer work, such as the early scene in which two men are pursued through the ocean by a broken-off portion of a wooden dock, thus providing one of the dumber and more distracting examples of Spielberg’s gambit of indicating the shark’s presence by objects moving on the ocean surface (apparently to cover up the fact that work on the mechanical shark wasn’t yet completed at the time of filming). I’d also argue that the opening sequence of a young woman attacked in the ocean by the unseen shark isn’t nearly as terrifying as it apparently was back in 1974, nor the shot of the submerged corpse head, a scene that was famously reshot by Spielberg for maximum effect but now seems rather silly (why did the shark leave the corpse intact?).

Yet overall JAWS remains a fun diversion, with spirited direction and first-rate performances by Roy Scheider as the harried Captain Brody and Robert Shaw as the hard-bitten seafarer Quint. Shaw is so good, in fact, that he makes what could have been a seriously ridiculous scene, of Quint getting devoured by the (patently fake) shark, seem horrific and genuinely tragic. Shaw is also purportedly responsible for Quint’s famous monologue about fighting sharks during the WWII-era wreck of the U.S.S. Indianapolis, dialogue that is generally credited to screenwriter John Milius but which JAWS’ scripter Carl Gottlieb claims was largely crafted by Shaw.

Let’s not forget the iconic score by John Williams, which uses a repeated two-note motif to wondrous effect, and justifiably famous dialogue like “We’re gonna need a bigger boat” and “That’s some bad hat, Harry,” lines that have inspired production companies (specifically the Toronto-based video outfit Bigger Boat Productions and Bryan Singer’s Bad Hat Harry Productions). The movie also contains what is arguably the screen’s most famous use of the “push” visual (meaning a simultaneous push in and zoom out) in an early scene in which Brody reacts to a shark kill.

The film’s arduous production, which took place in Martha’s Vineyard and the adjoining sea, was chronicled in two books, both  published in 1975: Carl Gottlieb’s THE JAWS LOG and Edith Blake’s THE MAKING OF THE MOVIE JAWS. Both are quite revealing, being relics of an era when movie making-of books contained real—and not always flattering—information about the films they chronicled (unlike the studio-vetted puff pieces we get nowadays). Of the two, the frequently republished JAWS LOG gets the nod, being a much starker and more succinct account. Note the portrayal of the Martha’s Vineyard’s locals in Blake’s book, who come off as unfailingly helpful and friendly to the production, while Gottlieb renders them as largely inhospitable. Gottlieb warns in his forward to THE JAWS LOG that his memory of the events he describes isn’t entirely reliable, yet I feel confident in proclaiming his book the definitive account of JAWS’ inception.

published in 1975: Carl Gottlieb’s THE JAWS LOG and Edith Blake’s THE MAKING OF THE MOVIE JAWS. Both are quite revealing, being relics of an era when movie making-of books contained real—and not always flattering—information about the films they chronicled (unlike the studio-vetted puff pieces we get nowadays). Of the two, the frequently republished JAWS LOG gets the nod, being a much starker and more succinct account. Note the portrayal of the Martha’s Vineyard’s locals in Blake’s book, who come off as unfailingly helpful and friendly to the production, while Gottlieb renders them as largely inhospitable. Gottlieb warns in his forward to THE JAWS LOG that his memory of the events he describes isn’t entirely reliable, yet I feel confident in proclaiming his book the definitive account of JAWS’ inception.

Incidentally, the movie’s massive success, in addition to creating the template for the summer blockbuster, can be credited with introducing Hollywood to the wonders of merchandising. If you were a kid in the late 1970s or early 80s you probably remember the plethora of JAWS inspired toys, games, lunch boxes, coloring books and so forth (although in my case it was JAWS 2 that provided all the ephemera), an odd occurrence given that JAWS, PG rated or not, was an intense horror movie, and the novel that inspired it a decidedly adult affair.

The Novel

JAWS was the debut novel by Peter Benchley. Published in February 1974, it can be viewed, together with James Herbert’s THE RATS and Berton Rouche’s FERAL (both of which also appeared in ‘74) as the inception of the “nasties” horror fiction subgenre, which as the 1970s wore on gave us man killing crabs, snakes, dogs, panthers and so forth. As related in THE JAWS LOG, the film rights to JAWS were snapped up by producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown before it was even published, and the novel’s subsequent monster success on the marketplace, which occurred while the movie was being filmed, was a pivotal reason Universal’s overseers refrained from pulling the plug on an increasingly chaotic production.

JAWS was the debut novel by Peter Benchley. Published in February 1974, it can be viewed, together with James Herbert’s THE RATS and Berton Rouche’s FERAL (both of which also appeared in ‘74) as the inception of the “nasties” horror fiction subgenre, which as the 1970s wore on gave us man killing crabs, snakes, dogs, panthers and so forth. As related in THE JAWS LOG, the film rights to JAWS were snapped up by producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown before it was even published, and the novel’s subsequent monster success on the marketplace, which occurred while the movie was being filmed, was a pivotal reason Universal’s overseers refrained from pulling the plug on an increasingly chaotic production.

These days, the central fascination of Benchley’s novel is its depiction of many of the conventions of the nasties subgenre in embryonic form. They include the bloody attacks on various clueless individuals (complete with mini-biographies of said individuals), the attempts by the virtuous hero to convince clueless authorities of the depths of the menace confronting them, and the final epic confrontation with that menace, which here takes the form of a boat manned by Quint, who had a previous encounter with sharks and so has a score to settle.

As he’d go on to prove in subsequent novels like THE DEEP and THE ISLAND, Benchley has a real talent for page-turning fiction, and JAWS remains a compelling piece of work. It contains much that’s not in the movie, and, frankly, in most cases that’s not such a bad thing. One example would be Brody’s clash with authorities that results in his cat being killed–an event that’s forgotten in the following chapter. Another is the fling Brody’s wife has with Brody’s colleague Hooper (the Richard Dreyfuss character in the movie), resulting in lines like “Sometimes she found that, without knowing it, she had been rubbing her hand over her vagina” that didn’t make it into the flick.

The Sequels

It’s inevitable that a movie as successful as JAWS would inspire sequels, and perhaps just as inevitable that those sequels  were of steadily decreasing quality. First was 1978’s JAWS 2, whose production was apparently even more arduous than that of its predecessor, and inspired a making-of book of its own: THE JAWS 2 LOG by Roy Lynd. That book isn’t on the same level as the first JAWS LOG, but it does contain some interesting tidbits, such as Lynd’s depiction of the drama that surrounded the firing of its initial director John Hancock. He was replaced by Jeannot Szwarc, who’s credited in THE JAWS 2 LOG for soldiering through a profoundly difficult production.

were of steadily decreasing quality. First was 1978’s JAWS 2, whose production was apparently even more arduous than that of its predecessor, and inspired a making-of book of its own: THE JAWS 2 LOG by Roy Lynd. That book isn’t on the same level as the first JAWS LOG, but it does contain some interesting tidbits, such as Lynd’s depiction of the drama that surrounded the firing of its initial director John Hancock. He was replaced by Jeannot Szwarc, who’s credited in THE JAWS 2 LOG for soldiering through a profoundly difficult production.

As a movie, unfortunately, JAWS 2, which remains most famous for its tagline “Just When You Thought it was Safe to go Back in the Water…,” isn’t much. Roy Scheider returns as Brody, along with Lorraine Gary as his wife. The shark action is more elaborate than that of the previous film, although the allegedly more sophisticated mechanical sharks on display fail to improve upon those of JAWS. Further problems include the uniformly bad acting by the largely adolescent cast and a ridiculous storyline that has a new shark menacing Brody’s son. This critter also sinks a helicopter and gets burnt up in perhaps the least convincing shark demise in movie history.

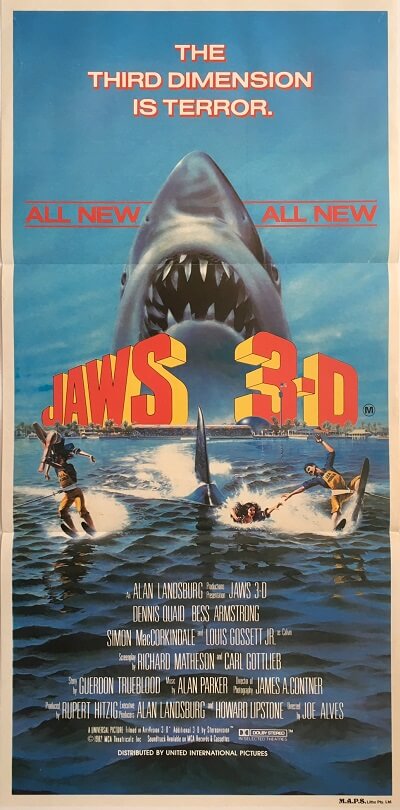

Ultimately the best I can say for JAWS 2 is that it’s better than JAWS 3-D. The latter took fi ve years to arrive, in the form of a shallow 3-D snooze-fest produced by TV titan Alan Landsburg and directed by Joe Alves, the production designer on the first two JAWS films. Given Alves’ amateur status as a director, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that the proceedings, set in a futuristic water park complete with spacious underwater quarters, are so dreary. What is surprising is that it was scripted by the great Richard Matheson, along with Guerdon Trueblood (of WELCOME HOME SOLDIER BOYS and THE CANDY SNATCHERS) and Carl Gottlieb, all of whom were capable of far better than JAWS 3-D’s limp and contrived excuse for a narrative.

ve years to arrive, in the form of a shallow 3-D snooze-fest produced by TV titan Alan Landsburg and directed by Joe Alves, the production designer on the first two JAWS films. Given Alves’ amateur status as a director, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that the proceedings, set in a futuristic water park complete with spacious underwater quarters, are so dreary. What is surprising is that it was scripted by the great Richard Matheson, along with Guerdon Trueblood (of WELCOME HOME SOLDIER BOYS and THE CANDY SNATCHERS) and Carl Gottlieb, all of whom were capable of far better than JAWS 3-D’s limp and contrived excuse for a narrative.

I’ll admit I thought JAWS 3-D seemed pretty cool during its initial 1983 release, but then I was around 9 years old at the time. These days I can see it for what it is: a flat-out disaster, with some of the worst special effects ever seen in a big studio production and unacceptably blurry visuals, whose consistency appears to have been irrevocably damaged by the conversion from 3-D to video.

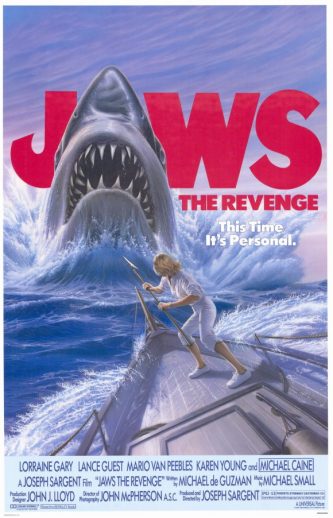

What could possibly be worse than JAWS 3-D? Try JAWS: THE REVENGE, which  appeared in 1987, and confirmed the rule that JAWS sequels only get steadily shittier. JAWS: THE REVENGE, in fact, is now regularly identified as one of the worst movies of all time, a classification with which I wholeheartedly concur.

appeared in 1987, and confirmed the rule that JAWS sequels only get steadily shittier. JAWS: THE REVENGE, in fact, is now regularly identified as one of the worst movies of all time, a classification with which I wholeheartedly concur.

JAWS: THE REVENGE posits that Chief Brody has died and his widow, again played by Lorraine Gary, moves to the Bahamas, but is pursued by a shark that apparently wants revenge because its relatives were killed by her hubbie. What follows are a succession of mostly bloodless, by-the-numbers shark attacks, perpetrated by a critter that looks even more cut-rate than those of the first three JAWS movies. The “special” effects are inexcusable, and not helped by director Joseph Sargent’s chaotic editing, or the fact that so many seemingly deceased characters always seem to inexplicably turn back up alive and well. Such a gambit worked in JAWS, when Richard Dreyfuss’s apparently dead Hooper unexpectedly popped up near the end, but not here. Steven Spielberg, after all, is a cinematic genius, while Joseph Sargent is Joseph Sargent.

The Knock-Offs

I’ll start this category with the never-made NATIONAL LAMPOON’S JAWS 3, PEOPLE 0, a quasi-spoof co-scripted by a young John Hughes. It was supposed to be National Lampoon’s follow-up to ANIMAL HOUSE (and the original JAWS 3), with direction by Joe Dante and Bo Derek as the leading lady. But after spending a reported $2 million on preproduction Universal pulled the plug, which producer Matty Simmons claims was at the behest of Mr. Spielberg, who apparently felt the script “demeaned” the property.

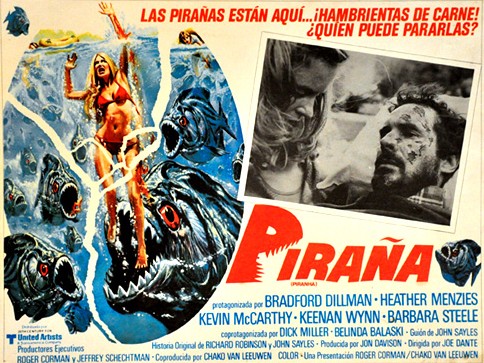

Spielberg did, however, stop Universal from filing suit against the Joe Dante directed Roger Corman production PIRANHA (1978), which with its account of mutant piranha invading a resort (and eventually the world’s oceans) was very clearly “inspired” by JAWS. In truth PIRANHA is probably the best of the JAWS wannabes (which isn’t saying much), benefiting from an inspired script by John Sayles and energetic helming by Dante, who worked under the direct tutelage of Steven Spielberg for much of the following two decades (in TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE, GREMLINS, INNERSPACE, GREMLINS 2 and SMALL SOLDIERS).

Spielberg did, however, stop Universal from filing suit against the Joe Dante directed Roger Corman production PIRANHA (1978), which with its account of mutant piranha invading a resort (and eventually the world’s oceans) was very clearly “inspired” by JAWS. In truth PIRANHA is probably the best of the JAWS wannabes (which isn’t saying much), benefiting from an inspired script by John Sayles and energetic helming by Dante, who worked under the direct tutelage of Steven Spielberg for much of the following two decades (in TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE, GREMLINS, INNERSPACE, GREMLINS 2 and SMALL SOLDIERS).

Not nearly as lucky was the 1981 Italian production THE LAST SHARK, a.k.a. GREAT WHITE, which Universal did successfully file suit against, getting it yanked from theaters. Having seen the film, I can assure you that early eighties moviegoers didn’t miss much! The 1976 atrocity MAKO: THE JAWS OF DEATH, an early release by the notorious Cannon Films, wasn’t much better, and nor was 1984’s DEVIL FISH. There was even a Bollywood take on the material in the form of 1996’s AATANK, which was even less inspired than THE LAST SHARK.

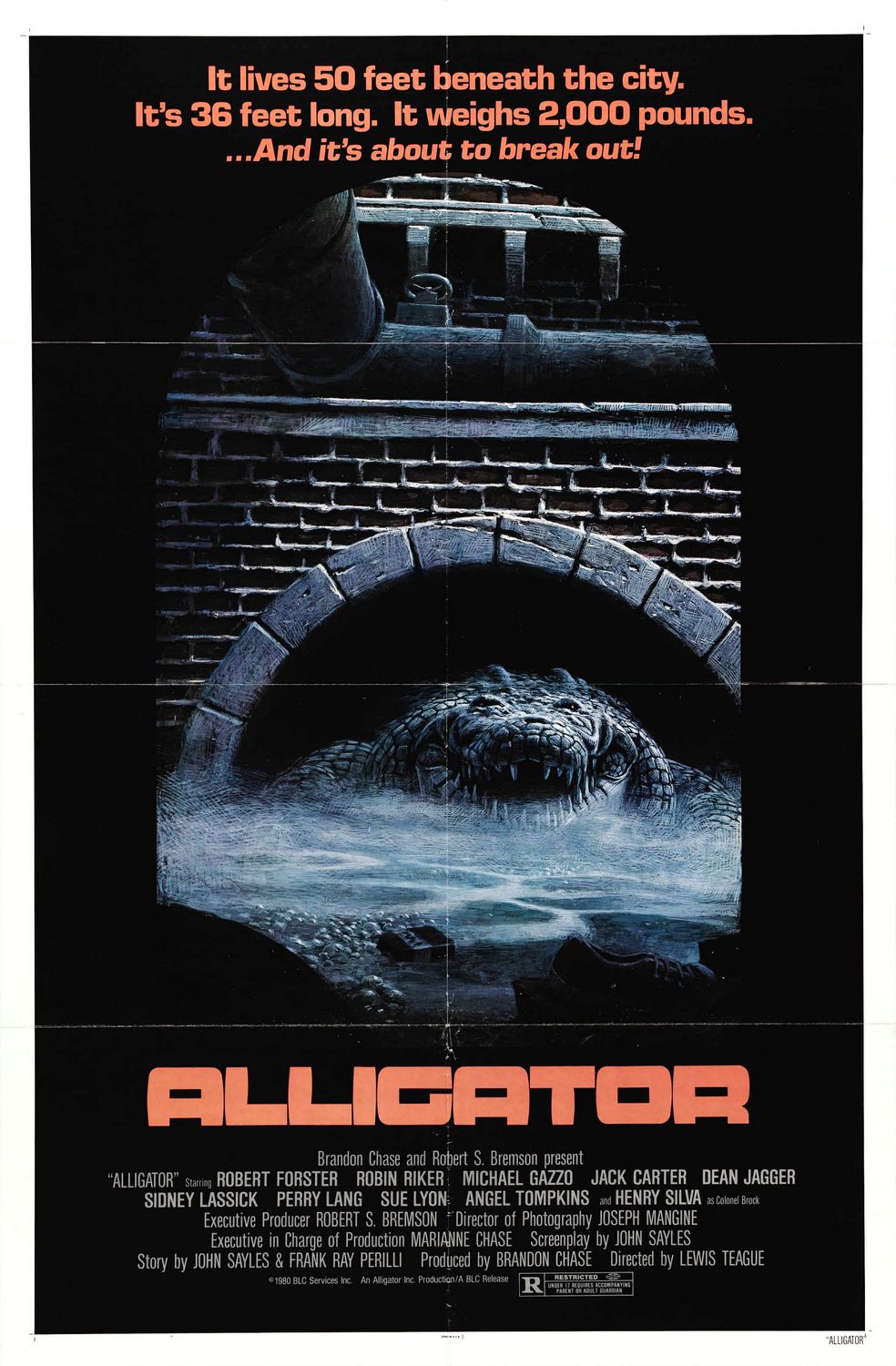

Less literal but just as evidently JAWS-like were 1976’s GRIZZLY, a.k.a. JAWS IN THE WOODS, and 1977’s ORCA, with a  killer whale substituting for JAWS’ great white. Likewise the bizarre Charles Bronson vehicle THE WHITE BUFFALO from 1977, in which Bronson plays Wild Bill Hickok hunting the titular shark stand-in, 1978’s BARRACUDA and the John Sayles scripted ALLIGATOR from 1980, which despite its R rating partook of the type of kid-friendly merchandising that accompanied JAWS’ release (I distinctly recall “Alligator–The Game,” whose players would place various objects in a plastic gator’s mouth until it closed, made by Ideal, which put out the similarly conceived “Game of Jaws”), as well as DOGS (1976), CLAWS and THE PACK (both 1977). Also in this category is ALIEN, which has been described, not inaccurately, as “JAWS in space.”

killer whale substituting for JAWS’ great white. Likewise the bizarre Charles Bronson vehicle THE WHITE BUFFALO from 1977, in which Bronson plays Wild Bill Hickok hunting the titular shark stand-in, 1978’s BARRACUDA and the John Sayles scripted ALLIGATOR from 1980, which despite its R rating partook of the type of kid-friendly merchandising that accompanied JAWS’ release (I distinctly recall “Alligator–The Game,” whose players would place various objects in a plastic gator’s mouth until it closed, made by Ideal, which put out the similarly conceived “Game of Jaws”), as well as DOGS (1976), CLAWS and THE PACK (both 1977). Also in this category is ALIEN, which has been described, not inaccurately, as “JAWS in space.”

More recently we’ve seen the Ronny Harlin directed DEEP BLUE SEA, featuring genetically modified sharks menacing the inhabitants of an undersea laboratory, and countless made-for-Syfy Channel movies about monster sharks, such as MEGA SHARK VS. GIANT OCTOPUS, SHARKTOPUS, SUPER SHARK and of course SHARKNADO, which has the distinction of being the most famous JAWS knock-off in existence. An interesting, and perhaps appropriate, situation: a Hollywood spectacular patterned on trash movie tropes begets just such a movie, whose best quality is that it’s not quite as abysmal as JAWS: THE REVENGE.