HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES is the title of the first volume of Charles Baudelaire’s renowned French translations of the writings of Edgar Allan Poe. This volume, first published in 1856, is credited with inspiring Poe’s exalted reputation in Europe, so it makes sense that HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES was the name given to not one but two French-made compilations of Poe-adapted films.

HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES is the title of the first volume of Charles Baudelaire’s renowned French translations of the writings of Edgar Allan Poe. This volume, first published in 1856, is credited with inspiring Poe’s exalted reputation in Europe, so it makes sense that HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES was the name given to not one but two French-made compilations of Poe-adapted films.

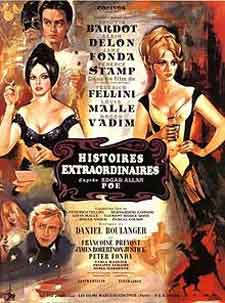

The first of those compilations turned up in 1968 in the form of a three-part feature (released in America as SPIRITS OF THE DEAD). It was one of several anthology films to emerge from Europe in the 1960s (see also BOCCACCIO 70, ROGOPAG, LOVE IN THE CITY, etc.), in which famed auteurs like Fellini, Pasolini, Godard, Malle and quite a few others marked time in between their feature film assignments.

HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES was conceived as a rival of sorts to the sixties-era Poe adaptations turned out by American International Pictures. The film, unfortunately, is bogged down by poor opening segments directed by Roger Vadim and Louis Malle, but the final part, courtesy of Federico Fellini, is a masterpiece.

Vadim’s segment, adapted from Poe’s “Metzengerstein,” is the worst by far, an anemic soft-core goth-fest involving feuding families and an untamed stallion. Not even the perverse spectacle of Peter and Jane Fonda playing lovers can save it from terminal dullsville. Malle’s “William Wilson,” which dramatizes Poe’s story of the same name, is only slightly better. Starring Alain Delon as a sadist tormented by an equally malicious double, it’s worth watching only to see Brigitte Bardot get whipped, although even this eye-popping sight is rendered disappointingly tame by modern standards.

Then there’s Fellini’s “Toby Dammit,” which is not only the film’s standout segment, but arguably one of Fellini’s greatest-ever works. Based (very loosely) on Poe’s “Never Bet Your Head to The Devil,” it’s a kaleidoscopic 30-minute trip through late-sixties Rome, with Terence Stamp as an alcoholic movie star filming an “Old Testament Western.” Especially noteworthy elements include an outrageous overcoat-and-scarf wardrobe that gives Stamp the look of a mod grim reaper, the ultra-creepy ghost girl who haunts him (inspired by a similar personage in Mario Bava’s OPERAZIONE PAURA/KILL BABY KILL), and Stamp’s final phantasmagoric drive on a one way ticket to oblivion. This is disorientation of an extremely high order, with a truly eye-popping color scheme and some unforgettably surreal imagery.

The precise relationship of the HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES film to the later TV miniseries of the same name is unknown (to me), but the series, broadcast in March through April of 1981, continues the format of the film, presenting six Poe adapted mini-films by varied directors. (It would also seem that 1980’s four-part FANTOMAS miniseries, which featured adaptations of the original FANTOMAS novels by Claude Chabrol and Juan Bunuel, both of whom went on to direct episodes of HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES, was an equivalent influence). The series was a French-Mexican co-production, which explains its mixture of French and South American filmmakers.

The precise relationship of the HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES film to the later TV miniseries of the same name is unknown (to me), but the series, broadcast in March through April of 1981, continues the format of the film, presenting six Poe adapted mini-films by varied directors. (It would also seem that 1980’s four-part FANTOMAS miniseries, which featured adaptations of the original FANTOMAS novels by Claude Chabrol and Juan Bunuel, both of whom went on to direct episodes of HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES, was an equivalent influence). The series was a French-Mexican co-production, which explains its mixture of French and South American filmmakers.

HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES’ first episode is Juan Bunuel’s “Le Joueur d’Echecs de Maelzel.” Its source is not a story but an essay, “Maelzel’s Chess Player” from 1836, about the phenomenon of the Turk, a chess playing automaton that took the world by storm in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In “Maelzel’s Chess Player” Poe offers his theories about this contraption (whose workings remain a mystery), deducing there was in fact a flesh-and-blood man inside the Turk who was carefully concealed from spectators.

Juan Bunuel situates this adaptation in his native Mexico, at a posh bourgeois party (of the type Bunuel’s father Luis loved to lampoon) wherein the Turk is shown to the bemused guests of a wealthy rancher. Its proprietors take time to open up panels on the figure to show that its insides are (or at least seem to be) mechanical, after which the thing is activated by a wind-up lever in its back. But the ruse is inadvertently exposed by a seductive woman with whom the little man inside the Turk becomes besotted.

The filmmaking, in keeping with Juan Bunuel’s feature film work, is noticeably unadventurous. Bunuel does, however, succeed in conveying the ideas advanced in Poe’s essay in a dramatic format, complete with a macabre denouement that justifies the pic’s inclusion in a series devoted to horror films–plus, the film’s presentation of the Turk, surely one of the most fascinating enigmas of the Victorian age, is an interesting and entirely convincing one.

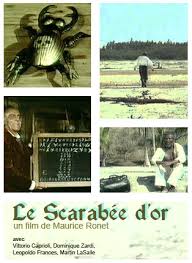

“Le Scarabee d’Or,” helmed by the veteran actor Maurice Ronet, was adapted from “The Gold Bug.” It was Poe’s most popular tale during his lifetime, and its story, about a search for buried treasure that incorporates a gold-plated insect, a skull’s eye-sockets and cryptography, remains a grabber.

“Le Scarabee d’Or,” helmed by the veteran actor Maurice Ronet, was adapted from “The Gold Bug.” It was Poe’s most popular tale during his lifetime, and its story, about a search for buried treasure that incorporates a gold-plated insect, a skull’s eye-sockets and cryptography, remains a grabber.

Ronet’s full-bodied recreation of the story’s tropical island setting is striking, particularly in the final scenes, in which the previously lush scenery becomes arid and desolate in the wake of a catastrophic storm. As in the previous episode, this one contains some added apprehension that wasn’t present in the story, involving an unseen murderer whose crimes make for a decidedly shocking finale.

The film, unfortunately, is quite bland and unexciting overall. The aforementioned storm, for instance, is signaled by some rudimentary howling wind sound effects and lighting flashes, a singularly weak rendition of extremely strong material.

Maurice Ronet once again took the directorial reigns for “Ligeia,” and the results are a bit more inspired overall. The scenery, comprised of an ancient cottage nestled amid a pastoral forest, is appropriately lush and forbidding, and captured in burnished lighting that gives every image a painterly sheen. Thus from a purely visual standpoint this film is a creditable adaptation of Poe’s darkly poetic account of grief and the supernatural. Indeed, the imagery on display here appears to have sprung full-blown from Poe’s text.

That text, however, is a problem when it comes to a film adaptation, as the story it weaves, involving a grief-stricken man (Georges Claisse) attempting to come to terms with the death of his wife (Josephine Chaplin), is decidedly uneventful. This is evident in all the schlepping around Claisse does throughout the film. As for the ending, in which Claisse’s deceased wife transforms into his former lover Ligeia (Arielle Dombasle) via a rudimentary dissolve effect, it’s not nearly as profound or chilling as it thinks it is. That transformation was presented in extremely subtle form in the story, and by depicting it so literally Ronet lessens the effect.

“Le Systeme du Docteur Goudron et du Professor Plume” was directed by the late Claude Chabrol, adapting Poe’s immortal  inmates-running-the-asylum tale “The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Fether.” It can safely be crowned the standout entry of HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES, boasting feature film-worthy staging and visual clarity.

inmates-running-the-asylum tale “The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Fether.” It can safely be crowned the standout entry of HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES, boasting feature film-worthy staging and visual clarity.

Jean-Francois Gerreaud plays a 19th Century everyman who one day decides to check out a secluded insane asylum whose head, one Doctor Maillard (Pierre Le Rumeur), has allegedly created a revolutionary new system for dealing with his inmates. After laying out the particulars of his system the doctor invites Gerreaud to a banquet whose participants behave in an increasingly irrational manner, and act terrified at the sounds emanating from a locked room. Eventually the truth is revealed: Maillard is in fact a patient who together with his fellow inmates locked up the doctors and took over the asylum.

Chabrol and screenwriter Paul Gegauff follow Poe’s text quite closely, and unlike previous adaptations of the story (which include Juan Lopez Moctezuma’s MANSION OF MADNESS and Janusz Majewski‘s SYSTEM), add very little of their own outside a coda in which the protagonist runs off with one of the loonies. And while the opening scenes are a bit overly talky, the whole thing rises to a memorable pitch of insanity, and overall must be counted as one of Chabrol’s most interesting films of the 1980s.

The Brazilian Cinema Novo maestro Ruy Guerra was the director of “La Lettre Volee,” which was based on “The Purloined Letter.” That’s an especially eccentric choice for a televised adaptation, given that the story is entirely dialogue-driven and has a narrative thrust that’s staunchly intellectual in nature. It should come as no surprise, then, that large portions of this film consist of men talking.

The most prominent of those men is the brilliant detective C. Auguste Dupin (Pierre Vaneck), who recounts how he discovered the whereabouts of a stolen letter containing compromising information by gaining entrance into the home of the man who stole it–where the letter was cleverly hidden in plain sight.

Guerra opens up the tale somewhat, with a variety of settings (as opposed to the story, which takes place entirely in a single room) that include a train cabin, a royal palace and a bullfighting ring. Guerra further jazzes things up with lively handheld camerawork, and includes brief allusions to Poe classics like “The Raven” and “The Cask of Amontillado,” making for a film that partially satisfies.

The final entry in HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES’ line up is “La Chute de la Maison Usher.” The director was Alexandre Austruc, who had previously adapted Poe’s “Pit and the Pendulum” for French television in 1964. For this outing Austruc tackled “The Fall of the House of Usher,” one of Poe’s most iconic texts. That may explain why “La Chute de la Maison Usher” is among the most lavishly deigned of HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRE’S segments, and also why it has the most prestigious cast, with Mathieu Carriere and Fanny Ardant in the lead roles of the doomed Roderick Usher and his equally doomed sister Madeline, with whom Roderick shares a possibly incestuous relationship.

The final entry in HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES’ line up is “La Chute de la Maison Usher.” The director was Alexandre Austruc, who had previously adapted Poe’s “Pit and the Pendulum” for French television in 1964. For this outing Austruc tackled “The Fall of the House of Usher,” one of Poe’s most iconic texts. That may explain why “La Chute de la Maison Usher” is among the most lavishly deigned of HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRE’S segments, and also why it has the most prestigious cast, with Mathieu Carriere and Fanny Ardant in the lead roles of the doomed Roderick Usher and his equally doomed sister Madeline, with whom Roderick shares a possibly incestuous relationship.

As with the previous segment, Austruc does much to open up the story, which is as hermetic and contained as anything Poe ever wrote. Gone is the atmosphere of claustrophobic oppression that pervaded the story, which Austruc essentially transforms into a gothic soap opera. As such it works reasonably well, hitting all the beats of Poe’s text and boasting strong performances by its principal actors. What it lacks is the type of visual pizzazz that might have put it over the top, and the revamped ending, which ignores the surreal conflagration that so memorably concluded the story, is uninspiring.

So the HISTOIRES EXTRAORDINAIRES TV incarnation has two episodes that work and four that only partially satisfy. The series and preceding film deserve credit, however, for their reverence to the work of Edgar Allan Poe, whose imaginings remain the benchmark for all modern horror.