That George A. Romero, who died on July 16, 2017, was one of the most important horror moviemakers of his generation, and indeed of all time, goes without saying. It also goes without saying that Romero was a familiar figure to horror nerds everywhere, to the point that he could almost be considered a family member.

That George A. Romero, who died on July 16, 2017, was one of the most important horror moviemakers of his generation, and indeed of all time, goes without saying. It also goes without saying that Romero was a familiar figure to horror nerds everywhere, to the point that he could almost be considered a family member.

…one of the most important horror moviemakers of his generation…

An unerringly friendly and gregarious individual, he was a ubiquitous presence at horror conventions and in the pages of Fangoria, with an appearance—initially as a burly fellow with a formidable beard and later as a skinny guy with oversized black rimmed glasses—that was instantly recognizable. His cameo appearance midway through SILENCE OF THE LAMBS was known to elicit cheers from horror buffs back in ‘91.

Of course, the true reason for Romero’s outsized media presence was a dispiriting one: throughout much of his nearly fifty year career he was chronically underemployed.

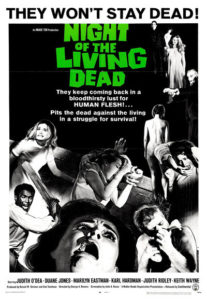

Things at least started out on a (very) high note with 1968’s NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. Much has been written about the impact of this seminal zombie-themed classic, including at least two books, several documentaries and endless dissertations both scholarly and otherwise. I won’t rehash their findings about NOTLD outside the bare perimeters: it was ground-breakingly gory and intense, and lensed in and around Pittsburgh, PA, which now claims the zombie as its “pet monster.”

Further NOTLD innovations included the casting of a black man (the late Duane Jones) in the lead role, and the extremely blatant allusions to the real-life upheavals of the late 1960s. Romero later claimed that latter factor was unintentional, although such thematic resonance would become a crucial element in his films.

Further NOTLD innovations included the casting of a black man (the late Duane Jones) in the lead role, and the extremely blatant allusions to the real-life upheavals of the late 1960s. Romero later claimed that latter factor was unintentional, although such thematic resonance would become a crucial element in his films.

A standout factor in NOTLD’s production was Romero’s stunningly poor business sense, manifested in the fact that he forgot to copyright the title NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, and so ended up with a public domain film. I’ve always believed business skills are indispensable to anyone working in the film business, yet Romero evidently never had much interest in or aptitude for the financial aspects of filmmaking. This, however, rendered him unique among his contemporaries (Carpenter, Hooper, Craven, etc.), among whom Romero was the only one who made exclusively personal films. In other words, he never worked as a director for hire, and only directed films he cared about.

Of those films, MARTIN and DAWN OF THE DEAD were bonafide masterpieces. Both appeared during Romero’s most prolific decade, the 1970s, and both bear the same copyright date: 1978. That’s despite the fact that the two films are quite different in tone and style, with the former being an understated vampire drama and the latter a raucous and satiric sequel to NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD.

Of Romero’s other 1970s productions, THERE’S ALWAYS VANILLA (1971) and SEASON OF THE WITCH (1972) are duds, but 1973’s THE CRAZIES is rather inspired, being a kinetic take on many of the themes introduced in NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, and continued in DAWN OF THE DEAD. The latter, I should add, marked an early and impressive showcase for SFX legend Tom Savini, who would go onto become one of Romero’s key collaborators.

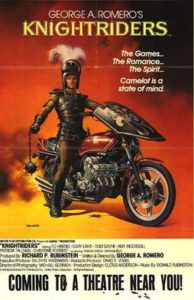

Trouble began with the release of KNIGHTRIDERS in 1981. An ambitious flop, its failure reportedly killed a number of projects Romero had in the pipeline. KNIGHTRIDERS, about a band of modern-day knights, isn’t bad, but it is unfocused and overlong, and, aside from Ed Harris in the lead role, is crippled by bad acting.

Trouble began with the release of KNIGHTRIDERS in 1981. An ambitious flop, its failure reportedly killed a number of projects Romero had in the pipeline. KNIGHTRIDERS, about a band of modern-day knights, isn’t bad, but it is unfocused and overlong, and, aside from Ed Harris in the lead role, is crippled by bad acting.

The Stephen King scripted CREEPSHOW (1982) has been vastly overrated in recent years (with many proclaiming it the “greatest horror movie ever made”), but it was a fun, gaudily stylized tribute to the horror comics of the 1950s. It was followed by the Romero-created anthology series TALES FROM THE DARKSIDE, which premiered in 1983 and ran from 1984-88.

KNIGHTRIDERS, CREEPSHOW and TALES FROM THE DARKSIDE were all produced by Laurel Entertainment, a company co-founded by Romero and Richard P. Rubinstein. Romero left the company in 1984, although Laurel still produced 1985’s DAY OF THE DEAD, the third entry in Romero’s DEAD saga. I remain lukewarm on the film, finding it an uninspired effort that was scaled down considerably from Romero’s original, far more extravagant conception (as revealed by an early draft screenplay contained on the Anchor Bay DVD). I will give props, though, to the gore effects of Tom Savini, which remain unsurpassed.

It took until 1988 for Romero to deliver another movie (not counting ‘87’s CREEPSHOW 2, which Romero scripted but didn’t direct), in the form of the so-so MONKEY SHINES, a could-have-been-good effort done in, once again, by bad acting.

I guess we shouldn’t be surprised that Romero grew so unprolific. His less-than-stellar business sense was out of place in an industry that in the 1990s grew increasingly corporatized and profit-driven. Following another scripting assignment on the 1990 anthology film TALES FROM THE DARKSIDE: THE MOVIE (which Savini has called “the real CREEPSHOW 3”), Romero’s nineties-era output consists of just two—actually one and a half—features.The first of those features was a segment of the 1990 two-parter TWO EVIL EYES (with the other helmed by Dario Argento), about which I’ll have to concur with the four word verdict of the late Gore Gazette: “Argento Shocks! Romero Sucks!” Romero followed it with the shockingly bland Stephen King adaptation THE DARK HALF in 1993, and a host of stalled projects (the cover of the 1994 paperback edition of the horror novel THE BLACK MARIAH by Jay R. Bonansinga proclaims that it’s “Soon To Be A Major Motion Picture Directed By George A. Romero,” which never materialized).

Romero’s next picture was 2000’s straight-to-DVD bummer BRUISER, a thoroughly uninspiring revenge drama. It seemed the great man’s career may have been nearing its end, as he was unable to find financing for his projects in the early ‘00s. I can recall seeing Romero speak at a 2004 Fangoria convention, where he showed concept art for a zombie musical he was trying to finance that frankly didn’t look too promising.

But then something completely unexpected happened: the 2004 DAWN OF THE DEAD remake and SHAUN OF THE DEAD debuted, and were quite successful. This had the effect of revitalizing the zombie genre, and suddenly the sixtyish George Romero, the undisputed grandfather of zombie cinema, was hot again.

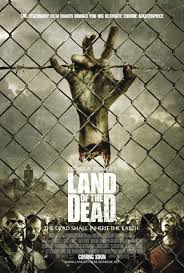

Romero capitalized on his newfound popularity by quickly putting LAND OF THE DEAD into production. The finished film was released in the summer of 2005, a little over a year after I saw Romero speak at that Fangoria convention (with the proposed zombie musical project mercifully discarded). It bears many telltale marks of the hastily made production it was, but LAND OF THE DEAD boasts some of the outsized scale of DAY OF THE DEAD’S initial conception, and overall was a most welcome return to form (although Mr. Savini was sadly not part of the production).

Romero capitalized on his newfound popularity by quickly putting LAND OF THE DEAD into production. The finished film was released in the summer of 2005, a little over a year after I saw Romero speak at that Fangoria convention (with the proposed zombie musical project mercifully discarded). It bears many telltale marks of the hastily made production it was, but LAND OF THE DEAD boasts some of the outsized scale of DAY OF THE DEAD’S initial conception, and overall was a most welcome return to form (although Mr. Savini was sadly not part of the production).

I wasn’t overjoyed with 2007’s DIARY OF THE DEAD, a jump on the found footage horror movie bandwagon. Aside from the now-requisite bad acting that plagued so many of Romero’s films, it’s marred by the fact that the zombie angle was clearly grafted onto other, unrelated themes that Romero wanted to explore. That was even truer of 2009’s SURVIVAL OF THE DEAD, essentially a so-so western that happened to feature zombies. SURVIVAL OF THE DEAD, unfortunately, was to be George A. Romero’s last film.

Following its release he relocated from his beloved Pittsburgh to Toronto, CA, and it was there that Romero passed on in 2017, leaving us with an uneven but quite distinctive body of work with three authentic masterpieces. That’s something few directors of any sort can claim, and nor can they hope to match the uncompromising commitment to his own personal vision that made Romero the standout genius he was and remains.

Following its release he relocated from his beloved Pittsburgh to Toronto, CA, and it was there that Romero passed on in 2017, leaving us with an uneven but quite distinctive body of work with three authentic masterpieces. That’s something few directors of any sort can claim, and nor can they hope to match the uncompromising commitment to his own personal vision that made Romero the standout genius he was and remains.