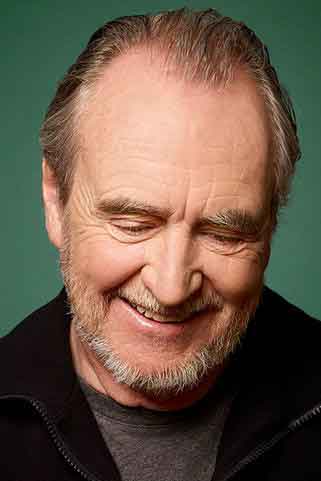

The shocking death of Wesley Earl Craven on August 30, 2015 has led me to conduct a serious reappraisal of his place in the horror firmament. As the title proclaims, I can say I honestly believe Craven is the most important horror moviemaker of his generation. I didn’t say the best, mind you, as I do admittedly have problems with many of his films (see point number 4), just the most important. Why? Here are five reasons:

The shocking death of Wesley Earl Craven on August 30, 2015 has led me to conduct a serious reappraisal of his place in the horror firmament. As the title proclaims, I can say I honestly believe Craven is the most important horror moviemaker of his generation. I didn’t say the best, mind you, as I do admittedly have problems with many of his films (see point number 4), just the most important. Why? Here are five reasons:

1. He made not one, but three iconic, era-defining horror films.

I’m referring, of course, to LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT, one of the seminal grindhouse flicks of the 1970s, A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, which introduced the most iconic horror movie icon of the 1980s, and SCREAM, which (unfortunately) impacted the 90s nearly as strongly.

NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 1984

NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 2010

2. He made many other interesting movies outside the big three

Craven’s other movies included one great film–THE HILLS HAVE EYES, which matched the ferocity of LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT, but with an added energy and intelligence–and some good tries. The latter category includes SHOCKER, which twisted the ELM STREET formula into a bizarre account of a serial killer immortalized after being executed via electric chair; THE SERPENT AND THE RAINBOW (below), in which Craven attempted, with modest success, to twist Wade Davis’ nonfiction bestseller about Haitian magic into a thoughtful genre piece; and THE PEOPLE UNDER THE STAIRS, an eighties political allegory in the form of a thoroughly warped thriller about an incestuous brother and sister holding children hostage in a corridor-packed house.

THE SERPENT AND THE RAINBOW 1988

Also deserving of mention are the five episodes of the 1980s revival of THE TWILIGHT ZONE directed by Craven, particularly “Shatterday,” “Wordplay and “Her Pilgrim Soul,” laudable pieces of dark fantasy all.

3. He captured the zeitgeist like no other filmmaker

Note the down-and-dirty 1970s aesthetic of LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT and THE HILLS HAVE EYES, and the slicker, more upscale Regan-era horrors of DEADLY BLESSING and A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET (I recall viewing those first two films after seeing ELM STREET for the first time, and finding it difficult to believe they were made by the same guy). Craven’s nineties films were likewise very much of their time, particularly NEW NIGHTMARE and SCREAM, which fit the postmodern bent of so much of that decade’s horror media, while the unpretentious old school thrills of 2005’s RED EYE were quite befitting of the retro vibe of the ‘00s.

4. He thrived despite churning out a ton of bad movies

See the ridiculous DEADLY FRIEND (in which LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE’S Matthew Laborteaux reanimates his dead girlfriend by inserting a robot computer chip into her brain, resulting in a film that’s about as good as it sounds) and the three deadening SCREAM sequels (it’s a sad fact that Craven’s final film was SCREAM 4)–and, for that matter, the original SCREAM, which for me managed to encapsulate everything that was annoying about the 1990s. In that same decade Craven gave us the horrendous Eddie Murphy vehicle VAMPIRE IN BROOKLYN, which is remembered only for the fact that a stuntwoman died during filming. The famously troubled production of 2005’s CURSED was likewise more memorable than the finished film–and the less said about MUSIC OF THE HEART, Craven’s fumbled attempt at Oscar bait, the better!

To borrow a quote from myself, “Wes Craven has always been a very erratic filmmaker.” True, but he was also an extremely resilient one who despite such failures always managed to stay at (or at least near) the top of the horror moviemaking heap.

“Wes Craven has always been a very erratic filmmaker.”

5. He used his educational background to good advantage

The idea of transposing Ingmar Bergman’s medieval revenge drama THE VIRGIN SPRING to early-1970s America in LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT was, it turned out, a brilliant one, as was Craven’s tweaking of the clueless-suburbanites-menaced-by-cannibals formula in THE HILLS HAVE EYES, whose protagonists (in contrast to those of the similarly themed TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE) actually fought back against their attackers. Craven’s concept for A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET wasn’t as original as some commentators have claimed, arriving as it did amid a glut of dream-based horror media, but it deserves credit for managing to stand out (of course I could argue that other examples of dream-horror, such as Ramsey Campbell’s 1983 novel INCARNATE and the flick DREAMSCAPE, released the same year as ELM STREET, were in fact superior, but never mind).

Incidentally, in scripting ELM STREET, Craven, harkening back to his early years as a literature professor, claimed he was inspired in part by Milton’s PARADISE LOST. Yes, knowledge IS a useful thing!

As a bonus, I’ll add another point, one that isn’t really valid in assessing Mr. Craven’s importance but has been remarked upon by seemingly everyone who met him:

6. He was a hell of a nice guy

I know that outside his movies I’ll always remember Wes Craven as a friendly and enthusiastic presence at horror conventions and on DVD commentaries. I think it goes without saying that he’ll be greatly missed.