Of the many authors to emerge from the horror boom of the 1970s, the late Ken Greenhall remains one of the most unfairly neglected—and also one of the most mysterious. Precious little is known about Greenhall’s life outside the basics: he was a retired professional when he commenced his writing career, which explains the concern with aging and death that suffuses his novels, and was possessed of a highly learned, questing mind, and a worldview that was decidedly bleak.

The fact that Greenhall was so unprolific in his output–-in the course of a 20 year career he published just six books–no doubt contributed to the widespread neglect that befell his novels. So too the fact that he never compromised the grimness of his vision: unlike the majority of his fellow horror scribes, Greenhall had little use for happy endings or leavening romance. The latter, in fact, was as destructive a force in his world as the horror business: as the narrator of Greenhall’s CHILDGRAVE proclaims, “I’ve been in love twice, and regardless of what you’ve heard elsewhere about the experience, I’m not sure I recommend it.”

But the most virulent factor in the neglect of Ken Greenhall’s fiction was likely much simpler. That factor, I contend, is the lurid cover art and misleading plot descriptions with which Greenhall’s publishers insisted on defiling his books.

Ken Greenhall’s first novel ELIZABETH, published in 1976 under the pseudonym “Jessica Hamilton” (his mother’s maiden name), was the least trashily packaged of his novels. I don’t know the reason Greenhall utilized a female pseudonym (which was also employed on the UK publications of his two subsequent novels), but ELIZABETH is one of the few truly convincing attempts by a male author at capturing the voice and thoughts of a member of the opposite sex.

Ken Greenhall’s first novel ELIZABETH, published in 1976 under the pseudonym “Jessica Hamilton” (his mother’s maiden name), was the least trashily packaged of his novels. I don’t know the reason Greenhall utilized a female pseudonym (which was also employed on the UK publications of his two subsequent novels), but ELIZABETH is one of the few truly convincing attempts by a male author at capturing the voice and thoughts of a member of the opposite sex.

Indeed, ELIZABETH’S primary selling point is its sinuous narrative voice, belonging to an unusually articulate fourteen-year-old girl who finds herself in contact with Francis, a long dead relative who practiced witchcraft while alive. Under Francis’ supernaturally endowed influence Elizabeth causes the deaths of her parents, her grandmother, her uncle James (who is admittedly in love with her) and her unborn child. Francis, it seems, comes in and out of Elizabeth’s life via a magic locket, which is stolen at least twice by a meddling woman who knows the heroine’s secret.

If this all sounds like a prime recipe for pulp horror, be advised that ELIZABETH is an unerringly elegant and refined affair. It may perhaps be a bit too refined for its own good, with a narrative that’s somewhat lacking in variety and invention. That’s a flaw Greenhall remedied quite dramatically in his next novel.

HELL HOUND appeared as a paperback original in 1977. It is, I believe, Ken Greenhall’s masterpiece, yet it received the tackiest cover art of any Greenhall novel, picturing a close-up of a barking dog with red eyes (the  corresponding dog’s eyes in the text are actually blue), and also a ridiculous tagline of the type for which its publisher, the notorious Zebra Books, was (in)famous: “A Thriller of the Surreal and the Supernatural!” (In the UK the novel appeared under the title BAXTER with more appropriate cover art).

corresponding dog’s eyes in the text are actually blue), and also a ridiculous tagline of the type for which its publisher, the notorious Zebra Books, was (in)famous: “A Thriller of the Surreal and the Supernatural!” (In the UK the novel appeared under the title BAXTER with more appropriate cover art).

But onto the novel itself, which is an unsung classic of the bizarre and grotesque that ranks with A CLOCKWORK ORANGE and THE WASP FACTORY. It’s the story of Baxter, a Bull Terrier who thinks like a human-–a profoundly nasty, brutish and vindictive human. Baxter’s thoughts are imparted via short first person chapters in which he invariably laments his current situation and attempts to find a way out of it.

As the novel opens, Baxter finds himself in the care of a lonely old woman who nauseates him. He takes to spying on a young couple next door, and gives the old bag a deadly spill down the stairs in order to be with them. Unfortunately the young wife is pregnant, which spoils things for Baxter, who doesn’t take well to the child once it’s born. He commits a second murder by drowning the kid in a backyard pond, which precipitates another, more fateful ownership change.

Baxter’s new owner is Carl, a Hitler-obsessed tyke who hangs out in a junkyard, where he’s created a miniature bunker in honor of his idol’s place of death. It seems that Baxter has at last found his ideal mate, but the boy and dog are a bit too much alike, leading to an inevitable showdown that only one of them will survive.

Around this twisted drama revolves a rich gallery of characters, including Carl’s clueless parents, a sympathetic teacher, a naive young girl, the latter’s callous father and a decrepit old man. It all adds up to an unflinchingly corrosive portrait of small-town America, and a narrative that functions as both an Orwellian satire of pet ownership in the modern world and a straightforward horror story about the wily nature of evil. It’s that rarity of rarities, a totally unique creation, and one that demands a critical appraisal (I would say reappraisal, but HELL HOUND doesn’t seem to have ever received its critical dues, pro or con, in the first place).

Incidentally, HELL HOUND was unique among Greenhall’s novels in that was adapted into a film. That film was the Jerome Boivin directed French production BAXTER, which faithfully replicated the novel’s demented narrative, and stands as a memorably bizarre concoction in its own right. But the material finds its fullest expression in HELL HOUND.

CHILDGRAVE was a fitting, if radically different, follow-up to ELIZABETH and HELL HOUND, a highly eccentric, supernaturally-tinged account of bad romance. Its narrator Jonathan Brewster is a widowed NYC photographer raising a five-year-old daughter. Jonathan meets the eccentric harpist Sara Coleridge at a concert and is immediately smitten. Sara entreats Jonathan not to involve himself with her but he can’t help himself—and neither can she. They’re in love, after all, which becomes the source of all the unpleasantness to come, and the primary reason this book is categorized as horror.

CHILDGRAVE was a fitting, if radically different, follow-up to ELIZABETH and HELL HOUND, a highly eccentric, supernaturally-tinged account of bad romance. Its narrator Jonathan Brewster is a widowed NYC photographer raising a five-year-old daughter. Jonathan meets the eccentric harpist Sara Coleridge at a concert and is immediately smitten. Sara entreats Jonathan not to involve himself with her but he can’t help himself—and neither can she. They’re in love, after all, which becomes the source of all the unpleasantness to come, and the primary reason this book is categorized as horror.

As this wholly eccentric affair commences, Jonathan notices a most inexplicable oddity in his photographs: long-dead people start turning up in them alongside the still-breathing subjects. This naturally attracts a lot of attention, and even a degree of fame. It’s that attention that drives Sara away at around the halfway point, leading Jonathan to track her to the secluded New York town where she grew up: a place called Childgrave.

The back cover plot description of the novel’s US edition makes Childgrave out to be far more prominent to the story than it actually is. In truth Childgrave serves essentially the same purpose as the imaginary kingdom of El Rey did in the final chapter of Jim Thompson’s THE GETWAWAY: a surreal purgatory where the amoral lovers at the novel’s center are forced to account for the recklessness of their actions. Jonathan is drawn to live in Childgrave due to his love for Sara, but the focus is on Jonathan’s young daughter Joanne. Childgrave, you see, is named after a young girl murdered in the area three hundred years earlier, which has given rise to a yearly tradition in which a girl aged 1-5 is sacrificed on Christmas Eve. The prospective victims are chosen by lottery, and Joanne, not yet having reached her sixth birthday, is among the candidates.

Along the way Greenhall provides a great deal of thoughtful discourse on subjects ranging from the bonds of community to the effects of religion, which prove nearly as destructive as the love affair that powers the story. Another Greenhall custom is the inconclusive ending, a resolution that seems entirely appropriate given the thoughtful and unsparing bent of CHILDGRAVE, which despite its surreal air is ultimately quite redolent of the conundrums and complexities of real life.

That last point is even more true of THE COMPANION, published in 1988. It’s centered on Jillian, a young woman who when not taking care  of her aging father serves as a near-death companion to old ladies. Jillian really loves her work, as is evident in the loving care she lavishes on her charges–and, as she candidly admits, the fact that those biddies’ lives always come to an end at Jillian’s hands. Told through Jillian’s enormously erudite first person recollections, THE COMPANION harkens back to ELIZABETH, which was also distinguished by its quintessentially feminine narration (it’s no accident, I’m guessing, that a pivotal character in the present novel is named Elizabeth).

of her aging father serves as a near-death companion to old ladies. Jillian really loves her work, as is evident in the loving care she lavishes on her charges–and, as she candidly admits, the fact that those biddies’ lives always come to an end at Jillian’s hands. Told through Jillian’s enormously erudite first person recollections, THE COMPANION harkens back to ELIZABETH, which was also distinguished by its quintessentially feminine narration (it’s no accident, I’m guessing, that a pivotal character in the present novel is named Elizabeth).

Unlike ELIZABETH, no supernatural rationale is present in THE COMPANION, with the true horror of the story being the attitude and worldview of Jillian, who is in fact a kill-happy sociopath—albeit an unusually bright and well-educated one whose frame of reference encompasses JANE EYRE, CITIZEN KANE, Duke Ellington, the consequences of the women’s liberation movement, the ravages of old age and the question of what lies beyond the boundaries of this life. The answers offered up, you can be sure, are anything but reassuring, with the possibility breached that in snuffing out her elderly charges Jillian may well be performing, as she repeatedly insists, a profound act of mercy and compassion.

Jillian’s latest companionship job is far more complicated than her past ones, as her newest charge, the ancient Elizabeth Dobbs, has a deeply eccentric, death-obsessed family. That’s particularly true of Elizabeth’s son David, who has a checkered past involving child abuse and gender confusion, and is clearly as deranged as Jillian herself. The Jillian-David conflict leads to some disappointingly conventional intrigue involving a lucrative inheritance and an attempted murder, but the concluding passages are appropriately dark and unsettled in a manner unique to Ken Greenhall.

THE COMPANION, I should add, appeared in the US as “Another Original publication of Pocket Books” (so proclaims the copyright page), complete with cover art and a plot summary that provide hyperbolic splatter movie artwork and descriptions, both of which completely miss the essence of the book.

DEATH CHAIN, which appeared as a paperback original in 1991, was Greenhall’s farewell to horror. At that point, of course, the horror boom had all-but dried up, and DEATH CHAIN definitely has a defeated, worn-out air to it, suggesting that Greenhall had had his fill of the scary stuff. It’s the weakest of his novels by far, and also the most overtly commercial (although Pocket Books managed to once again completely miss the ball packaging-wise, providing cover art and a back cover synopsis more befitting of a Christopher Pike potboiler).

DEATH CHAIN, which appeared as a paperback original in 1991, was Greenhall’s farewell to horror. At that point, of course, the horror boom had all-but dried up, and DEATH CHAIN definitely has a defeated, worn-out air to it, suggesting that Greenhall had had his fill of the scary stuff. It’s the weakest of his novels by far, and also the most overtly commercial (although Pocket Books managed to once again completely miss the ball packaging-wise, providing cover art and a back cover synopsis more befitting of a Christopher Pike potboiler).

It has, at least, a promisingly demented premise: a chain letter is sent to several emotionally disturbed residents of a small town, commanding each to kill a stranger. What results, however, is a deadening concoction, with a meandering narrative whose main plotline is frequently dropped so Greenhall can explore the emotional life of his protagonist, an aging painter who ends up solving the mystery of the letter’s origins; Greenhall evidently believed this character, who was likely more than a shade autobiographical, is far more interesting than he actually is.

The suspense-free climax, with its silly Scooby Doo-esque reveal, rounds things out on a ho-hum note.

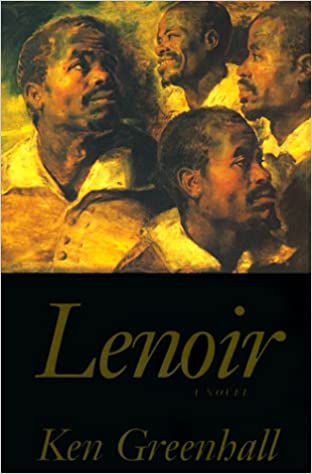

For LENOIR, published in hardcover by Zoland Books in 1998, Ken Greenhall provided an interesting and solidly researched historical saga. You’ll have a hard time finding any thematic links with his previous fare in this book, outside a dedication to BAXTER’S director Jerome Boivin and a cameo appearance by the canine protagonist of that film/novel.

Like Tracy Chevalier’s better-known GIRL WITH A PEARL EARRING, LENOIR (which actually preceded Chevalier’s novel by a year) takes a  famous painting and imagines what its subject’s life might have been like. The artwork in question is Peter Paul Rubens’ early 17th Century painting “Four Studies of Head of a Negro,” depicting an unidentified man’s face wearing four different expressions.

famous painting and imagines what its subject’s life might have been like. The artwork in question is Peter Paul Rubens’ early 17th Century painting “Four Studies of Head of a Negro,” depicting an unidentified man’s face wearing four different expressions.

The book’s first person protagonist Lenoir is alleged to be the model for the painting. He’s a highly erudite slave in seventeenth century Amsterdam who’s owned by Mr. Twee, a kind-hearted rouge who allows Lenoir to live in the manner of a free man.

In the course of the novel Lenoir poses for paintings by Rembrandt, flees to Antwerp after being accused of practicing murderous sorcery, briefly joins a traveling acting troupe and works for the aforementioned Mr. Rubens until the latter’s death. Throughout it all Lenoir registers as a finely constructed personage, with entirely convincing reactions to the strange world he finds himself thrust into.

Less enchanting is the narrative, which could frankly be a bit more lively. Considering all the turmoil that occurred during the time of LENOIR’S setting, I think I’m justified in expecting a bit more from an account that’s lively yet ultimately a bit too dry for its own good.

LENOIR, unfortunately, appears to be Ken Greenhall’s final novel. Even more unfortunate is the fact that it, and indeed all his novels, are now long out of print, with little-to-no effort being made to reprint them. Yet I can promise that tracking down copies of ELIZABETH, HELL HOUND, CHILDGRAVE, THE COMPANION and LENOIR—and, if you absolutely must, DEATH CHAIN—will be well worth the while of any true horror fan.