Blockbuster (formerly Blockbuster Video) has, as of early 2013, been in the news a lot recently, and that news has not been encouraging. It seems that every few weeks more Blockbuster stores are closed and more employees laid off. At present there are less than 500 Blockbuster outlets in the United States, as opposed to the 9,000-plus units Blockbuster claimed as its height in 2004, and I expect that number will shrink even more in the coming months.

Blockbuster (formerly Blockbuster Video) has, as of early 2013, been in the news a lot recently, and that news has not been encouraging. It seems that every few weeks more Blockbuster stores are closed and more employees laid off. At present there are less than 500 Blockbuster outlets in the United States, as opposed to the 9,000-plus units Blockbuster claimed as its height in 2004, and I expect that number will shrink even more in the coming months.

Yet for all its current troubles Blockbuster is still the world’s top video rental chain, having outlasted all of its competitors. Founded in 1985, Blockbuster had a profound effect on the entertainment industry during its twenty year heyday, and the horror industry in particular.

The Early Days

Upon seeing Blockbuster’s flagship store in Texas, future Blockbuster franchisee Scott Beck gushed that it “was like IBM and McDonald’s had opened a video store” with its increased selection of new release titles, computerized check-out process and three-day rental period (back in ‘85 two-night intervals were the standard). Blockbuster is also credited with customizing its inventory to meet the needs of various communities, although I question the accuracy of that assessment.

It’s a fact that from the start Blockbuster refused to stock X-rated videos (because, in the words of Blockbuster honcho David Cook, “we don’t care if people watch pornography, we just don’t want to sell it to you”) and most anything deemed controversial. THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST fell into that category, as did Peter Greenaway’s THE COOK, THE THIEF, HIS WIFE AND HER LOVER, Pedro Almodovar’s TIE ME UP! TIE ME DOWN! and much of the filmography of action director Walter Hill (THE WARRIORS, SOUTHERN COMFORT, etc.). Worse, as its bottom line was hit by overexpansion (it was estimated that at its peak Blockbuster opened a new store every 24 hours) and the overall video industry slump of the early 1990s, Blockbuster narrowed its inventory considerably, with a moratorium on anything that wasn’t a mainstream Hollywood product.

Blockbusting in the 1990s

It being the biggest video rental chain in the land, Hollywood took definite notice of Blockbuster’s family friendly preferences. The newly minted NC-17 (adults only) rating, kicked off with the 1990 release of HENRY AND JUNE, was supposed to usher in a new era of adult entertainment that was stopped in its tracks, in no small part because Blockbuster refused to stock anything greater than an R rating. Horror fans, meanwhile, had to make do with watered-down crap like THE PUPPET MASTERS and MARY SHELLEY’S FRANKENSTEIN, both of which bore definite signs of Blockbuster-influenced sanitization.

But on the other hand the nineties contained a thriving independent film scene that was ill-served by Blockbuster, whose exclusionary policies provided its competition with an easy niche to fill. That competition included the numerous bootleg video outfits that sprung up throughout the decade selling uncut versions of films that Blockbuster carried only in censored form, as well as rival chains like Tower Video that stocked movies Blockbuster didn’t, and the countless independently owned “mom and pop” video stores that thrived despite Blockbuster’s attempts at taking them down. Scott Beck lamented this situation at a 1991 cable trade show, conceding that (referring to independently owned video stores) “We’ve done our best to eradicate as many as we can, but they just stick with it.”

An example of just such an attempted eradication occurred in my hometown of Manhattan Beach, home to the late Video Archives. In 1989 Blockbuster, as was its custom, opened up a store less than a block north of Video Archives and then, when the latter continued to hold its ground, another store two blocks south of the Archives–-which, as Beck lamented, continued to “just stick with it.” (For the record, Video Archives moved to another town in 1994, where it closed down under circumstances that remain mysterious).

Throughout the 1990s you could always count on finding a Blockbuster near just about any independent video store, in or out of the U.S. While living in Vancouver, BC in the mid-nineties I patronized Videomatica, a video store that was nearly as revered as Video Archives that, unsurprisingly, had to contend with a Blockbuster situated directly across the street. Both stores are now closed, but it was the Blockbuster that went down first!

I should add here that despite Blockbuster’s competitive bent (made clear in their TV commercial slogan “Wow! What a Difference!”) the concept of competitive pricing was evidently foreign to its overseers. Much was made of the fact that Blockbuster didn’t charge the type of membership fees most other video stores did, yet its rental costs were ludicrously high. Back in 1989 a friend of mine claimed he tried to rent a couple Nintendo games at the aforementioned Manhattan Beach Blockbuster, only to leave the games on the checkout counter and walk out upon finding that the cost exceeded eight dollars.

The Viacom Years

The Viacom Years

Things turned around in the mid-nineties, when Blockbuster was acquired by Viacom. The acquisition was presided over by Viacom CEO Sumner Redstone, who engineered a lucrative revenue sharing policy with the major studios. Under this system Blockbuster purchased new release videos at a fraction of what its competitors were charged, and kept a 60 percent rental fee. Redstone also reportedly used Blockbuster’s video rentals to determine what movies Paramount Pictures, another Viacom property, would greenlight. (This explains why so many of Paramount’s late-90s/early-00 releases were cheaply made clones of previous movies-–see the BATMAN wannabe THE PHANTOM, the JURASSIC PARK wannabe THE RELIC, the ARMAGEDDON wannabe THE CORE, etc).

In addition, there was the 1992 instituted Blockbuster Music store chain and “Block Party” entertainment complexes that turned up in a couple of states in ‘94, consisting of mini-amusement parks housed in massive city block-sized buildings. Viacom even relaxed Blockbuster’s family friendly stance somewhat, stocking the uncut version of Clive Barker’s 1995 gruefest LORD OF ILLUSIONS (due apparently to Barker’s own powers of persuasion) and lifting the ban against THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST.

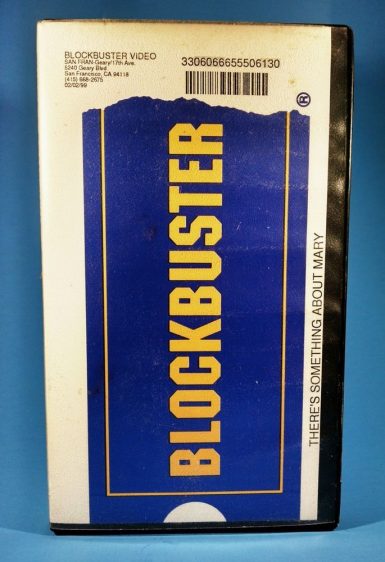

By the late 1990s it seemed Blockbuster was set for world domination. In the summer of 1998 even I was persuaded to venture inside Blockbuster’s much-hated walls due to a massive sell-off of old VHS tapes, including quite a few lucrative collector’s items, at a cost of just $1-$5.00 a pop (possibly the only time in its history when Blockbuster product was reasonably priced). Even the DVD revolution of the early ‘00s didn’t appear to phase Blockbuster, which handled the switch from VHS to DVD with little-to-no evident strain.

The Dissolution

It’s understandable that Blockbuster failed to see the end coming. Nobody else did, either. The DVD rental-by-mail service Netflix was founded in 1997 and failed to post a profit until 2003, yet from there it quickly caught on, and by 2005 was shipping out a reported 1 million DVDs every day. There was also the retail kiosk outfit Redbox, which opened in 2002 and within a few years had more U.S. locations than Blockbuster.

By the mid-00s Blockbuster, having separated from Viacom in 2004, found itself in the beleaguered-underdog position in which it had put its competitors during the previous decade. Blockbuster still wielded a fair amount of power over the entertainment landscape, with its June 2007 decision to go with Blu-ray over HD DVD having a definite effect on how that particular rivalry played out (note that we no longer speak of HD). That, however, didn’t reverse the slide, and in September 2010 Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy. In April 2011 it was purchased by Dish Network, which made grandiose statements about increasing  Blockbuster’s profitability that have yet to come to fruition. Blockbuster is still in operation, but I strongly doubt it will be for much longer.

Blockbuster’s profitability that have yet to come to fruition. Blockbuster is still in operation, but I strongly doubt it will be for much longer.

(2020 postscript: right now just one Blockbuster outlet exists in the entire world)

Finally…

What can we take away from the Blockbuster debacle? For starters, I believe it’s clear that consumers will seek out the types of movies they want regardless of what Blockbuster’s honchos, or anyone else, dictates. It’s also clear that no organization is inviolate, regardless of how big or entrenched it may seem. I’d say the big question now is what direction (if any) will home video take in the coming years? Obviously only time will tell, but here’s something I can predict: whatever occurs in home video realm, Blockbuster, for the first time in ages, will not be a part of it.