Remember the Cannon Group? It was a small-time movie studio purchased in 1979 by the Israeli duo Menahem Golan and Yorum Globus, who quickly turned Cannon into one of the most prolific and ambitious film conglomerates of the 1980s. During its short lifespan (which lasted a little over a decade) the Golan-Globus manned Cannon Group produced and/or distributed around 150 films and operated three major European theater chains. Cannon, in short, was a fixture of the eighties movie scene, which for me was greatly enriched by its flamboyant and irrepressible spirit.

Remember the Cannon Group? It was a small-time movie studio purchased in 1979 by the Israeli duo Menahem Golan and Yorum Globus, who quickly turned Cannon into one of the most prolific and ambitious film conglomerates of the 1980s. During its short lifespan (which lasted a little over a decade) the Golan-Globus manned Cannon Group produced and/or distributed around 150 films and operated three major European theater chains. Cannon, in short, was a fixture of the eighties movie scene, which for me was greatly enriched by its flamboyant and irrepressible spirit.

Among Cannon’s accomplishments, some of them laudatory and some not-so, were the formation of the ninja movie craze (with the Golan helmed ENTER THE NINJA) and the careers of Chuck Norris and Jean-Claude Van Damme, as well as the post-POLTERGEIST employment of director Tobe Hooper (with LIFEFORCE, THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE 2 and INVADERS FROM MARS) and the American career of Russian filmmaker Andrei Konchalovsky (who directed MARIA’S LOVERS, RUNAWAY TRAIN and several other Cannon productions). Cannon, unfortunately, also presided over two of the hairiest real-life film set accidents of all time, on the sets of BRADDOCK: MISSING IN ACTION III and DELTA FORCE II—the respective tragedies both involved fatal helicopter crashes in the Philippines, where lax safety standards and Cannon’s corner-cutting set management made for a deadly combination.

The only book about the Cannon phenomenon that I know of is HOLLYWOOD A GO-GO by Andrew Yule, a staunchly  business-minded study published by Sphere in 1987. Yule opens the book with the claim that “the films produced since Cannon’s formation arguably includes some of the shoddiest fare ever foisted on the public.” Obviously this is a highly biased account, with Yule portraying Golan and Globus as shameless hucksters who kept their empire going through inflated figures, subterfuge and old-fashioned bullcrap. Yule’s claims, it must be said, are persuasive, and backed up by copious lists and charts delineating Cannon’s consistent non-success.

business-minded study published by Sphere in 1987. Yule opens the book with the claim that “the films produced since Cannon’s formation arguably includes some of the shoddiest fare ever foisted on the public.” Obviously this is a highly biased account, with Yule portraying Golan and Globus as shameless hucksters who kept their empire going through inflated figures, subterfuge and old-fashioned bullcrap. Yule’s claims, it must be said, are persuasive, and backed up by copious lists and charts delineating Cannon’s consistent non-success.

Precious little info is provided on Golan and Globus’ early years, with a scant twelve pages devoted to G&G’s time before they took over the Cannon Group. We learn that in the late 1960s Golan worked for Roger Corman, from whom he learned the principals of budget-lite moviemaking; from there Golan got together with the staunchly business-minded Globus, and the two made a string of Israeli lensed no-budgeters. Once ensconced at Cannon they cranked out low budget movies at a rate of around two dozen a year, ensuring a steady stream of product that helped mask the fact that very few of those films ever turned a profit.

I’ll dispute the “shoddiest fare ever foisted on the public” proclamation. Yes, Cannon put out a lot of crap in its day, but so did Paramount, Warner, Columbia, Universal, 20th Century Fox and Disney (take it from one who came of age in the eighties: anyone who proclaims that decade a “golden age” for movies is full of shit). As for good movies, Cannon gave us RUNAWAY TRAIN, SHY PEOPLE, POWAQQATSI, 52 PICK-UP, BARFLY and FOOL FOR LOVE, as well as irresistible guilty pleasures like THE APPLE, NINJA III: THE DOMINATION, MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE and LIFEFORCE.

Cannon developed a definite little-company-that-could prestige in the late eighties, when Golan and Globus attempted to make over the company as a prestigious art movie outfit. Roger Ebert went so far as to make Golan the “hero” of his 1987 Cannes notebook TWO WEEKS IN THE MIDDAY SUN (Andrews and McMeel), asserting that “no other production organization in the world today—certainly not any of the seven Hollywood “majors”—has taken more chances with serious, marginal films than Cannon,” which was apparently “the single most important entity at Cannes.”

Cannon developed a definite little-company-that-could prestige in the late eighties, when Golan and Globus attempted to make over the company as a prestigious art movie outfit. Roger Ebert went so far as to make Golan the “hero” of his 1987 Cannes notebook TWO WEEKS IN THE MIDDAY SUN (Andrews and McMeel), asserting that “no other production organization in the world today—certainly not any of the seven Hollywood “majors”—has taken more chances with serious, marginal films than Cannon,” which was apparently “the single most important entity at Cannes.”

It was at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival that Cannon premiered BARFLY and SHY PEOPLE, as well as TOUGH GUYS DON’T DANCE and Jean Luc Godard’s KING LEAR (the latter remains infamous for the fact that Golan wrote out a contract for it on a dinner napkin). According to Ebert, “Golan and Globus are possibly the only producers in the world who enter Cannes every year as if it were a competition, an athletic event.” Yet, as happened every year, none of Cannon’s 1987 entries won the top prize at the festival, and nor were any of those films a financial success (a wiseass journalist pointed out that the napkin on which Golan scribbled the contract for KING LEAR would probably bring in more money than the film itself, which wasn’t far from the truth). That of course didn’t stop Golan from proclaiming to Newsweek that Cannon was “outperforming” all the major studios.

But people inevitably caught onto Cannon’s ruse. It’s a fact that by the time of its 1993 demise Cannon was a veritable laughing stock. By that point, of course, Cannon had been purchased by Pathe Communications and Golan and Globus had split up, with Globus running the Pathe-owned Cannon Group and Golan manning the short-lived 21st Century Productions.

I got a first-hand glimpse of the anti-Cannon sentiment at a 1993 UCLA screening of POWAQQATSI with live orchestral accompaniment, at the beginning of which the conductor was momentarily thrown off by all the derisive snickers that greeted the Cannon logo. Clearly, any prestige Cannon might have generated in its day was long gone.

Now, two decades later, the Cannon saga seems eerily prescient. Consider: back in the eighties Hollywood was scandalized by the fact that Cannon was manned by two bull-headed men who never relinquished their positions—in other words, the Bob and Harvey Weinstein of their time. Like the Weinsteins, Golan and Globus alternated art house and exploitation films, all of which they boldly released alongside those of the so-called majors (the major difference, of course, is that the Weinsteins actually achieved some commercial success).

Even more prescient, and troublingly so, was Cannon’s much-derided practice of gearing their publicity toward the opening weekend, when, it was opined, their movies would make the lions’ share of their fortune before bad word of mouth did them in. That strategy, of course, is now standard procedure in Hollywood.

You can also find an eighties-era foreshadowing of Hollywood’s current obsession with revamped fairy tales in the “Cannon Movie Tale” cycle of 1987-89. Conceived, apparently, as a cheap way to compete with Disney (fairy tales are in the public domain, meaning Cannon didn’t have to pay writers’ royalties), these films, nine in all (sixteen were planned), were filmed mostly in Israel on identical sets. The best of them, according to Golan himself, was 1987’s BEAUTY AND THE BEAST with John Savage and Rebecca de Mornay.

Perhaps the most noteworthy development in the Cannon saga is the remarkable upswing of its rep utation. In contrast to those derisive snickers I heard back in ‘93, modern filmmakers and film buffs tend to look back at Cannon’s films with fond nostalgia—and to view the Cannon business model as one to be emulated. This was proven at an independent filmmakers’ panel at an October 2010 Burbank horror convention, at which several of the panelists named Cannon as their primary inspiration.

utation. In contrast to those derisive snickers I heard back in ‘93, modern filmmakers and film buffs tend to look back at Cannon’s films with fond nostalgia—and to view the Cannon business model as one to be emulated. This was proven at an independent filmmakers’ panel at an October 2010 Burbank horror convention, at which several of the panelists named Cannon as their primary inspiration.

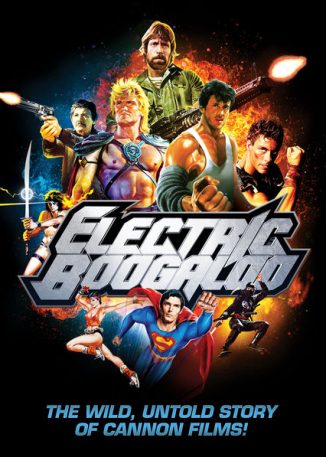

Further Cannon worship is promised in a soon-to-be-released documentary by Mark (NOT QUITE HOLLYWOOD) Hartley entitled ELECTRIC BOOGALOO: THE WILD, UNTOLD STORY OF CANNON FILMS, whose release will coincide with traveling roadshow screenings of many of Cannon’s signature films. Critical though I am of Cannon and its cut-rate practices, I can’t say I don’t miss it, and will doubtless be among the first in line for ELECTRIC BOOGALOO and the roadshow screenings. Long live the Cannon Group!