Q: What do THE MARTYR by David Meltzer, LET’S GO PLAY AT THE ADAMS’ by Mendal Johnson and THE GIRL NEXT DOOR by Jack Ketchum have in common? A: They’re among the most profoundly disturbing novels of their respective decades. All three publications have been widely misunderstood and unfairly marginalized, packaged as trashy horror programmers (and in the case of THE MARTYR as a fuck book) when in fact they’re far more than that.

This infernal trio has at least one definite link in the fact that all three novels were inspired by the same real-life crime. That crime was committed in 1965 against 16-year-old Sylvia Likens, who was tortured to death in suburban Indiana by her guardian Gertrude Baniszewski, together with the latter’s seven children and several neighborhood kids. Media inspired by the case include the nonfiction INDIANA TORTURE SLAYING by John Dean, Patte Wheat’s docu-novel BY SANCTION OF THE VICTIM, Kate Millet’s “Meditation on a Human Sacrifice” THE BASEMENT, and the 2007 film AN AMERCIAN CRIME.

By contrast, the three novels under discussion are heavily fictionalized dramatizations. Yet I believe they’re superior to their fellows, both as studies of the Sylvia Likens murder—from which Meltzer, Johnson and Ketchum each mine dark truths that Wheat, Millet and co. miss—and as superbly drafted exercises in unrelenting psycho-horror.

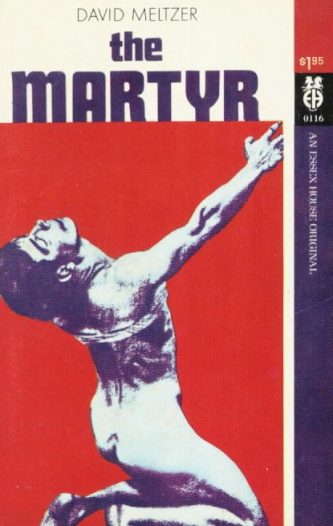

THE MARTYR by David Meltzer had its first and thus far only publication in 1969, courtesy of the late Essex House (publishers of “the very finest in adult reading by the most provocative modern writers”). The novel‘s setting is suburban U.S.A. where the teenaged Rebecca and her brother Jeremy are sent by their traveling singer parents to live with their aunt Lorna and her kids Nina and Ricky. Lorna is a bitter, piously religious widow who none-too-secretly detests her nephews, Rebecca in particular. Lorna is particularly upset that years earlier Rebecca was molested by Lorna’s late husband, for which she’s never forgiven either of them.

THE MARTYR by David Meltzer had its first and thus far only publication in 1969, courtesy of the late Essex House (publishers of “the very finest in adult reading by the most provocative modern writers”). The novel‘s setting is suburban U.S.A. where the teenaged Rebecca and her brother Jeremy are sent by their traveling singer parents to live with their aunt Lorna and her kids Nina and Ricky. Lorna is a bitter, piously religious widow who none-too-secretly detests her nephews, Rebecca in particular. Lorna is particularly upset that years earlier Rebecca was molested by Lorna’s late husband, for which she’s never forgiven either of them.

As for Jeremy, he’s severely injured in a movie theater brawl and winds up confined to a room in Lorna’s house, unable to move his legs. As it turns out, he’s far luckier than his sister.

Upon beating Rebecca with a belt buckle and finding the act “strangely exciting,” Lorna’s latent sadism is inflamed, and she initiates a campaign of beatings in the belief that she’s doing God’s work. The abuse inevitably escalates, with Nina, Ricky and several neighborhood boys invited to join in the madness, which culminates in Lorna’s basement.

In Meltzer’s pitiless vision nobody is innocent. This includes Jeremy, who grows so remote and self-centered he stops paying attention to his sister’s torment, and Rebecca herself, who like everyone else in her orbit falls under Lorna’s evil spell.

Being a prolific poet, Meltzer packs the text with snatches of self-penned poetry and utilizes a freeform prose style (there are no quotation marks) that grows extremely descriptive at times. Meltzer is also quite canny in his pitiless explorations of the fatal link between sexuality and violence, the potentially deadly effects of parental influence, the dangers of religion, the latent evils of American suburbia and many other troubling topics, all packed into a short yet starkly powerful gut punch of a novel.

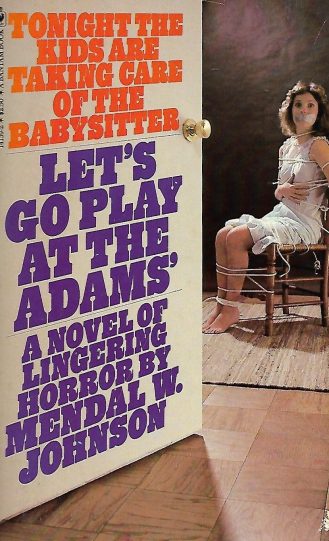

1974’s LET’S GO PLAY AT THE ADAMS’ was the only novel by the late Mendal Johnson. Of the three publications discussed  here this one deviates most from the particulars of the Sylvia Likens murder. Indeed, it’s debatable whether Johnson was directly influenced by the case, yet his portrayal of a group of children drawn into a web of evil and depravity centered on an attractive young woman would seem to have a definite connection.

here this one deviates most from the particulars of the Sylvia Likens murder. Indeed, it’s debatable whether Johnson was directly influenced by the case, yet his portrayal of a group of children drawn into a web of evil and depravity centered on an attractive young woman would seem to have a definite connection.

Here two bratty kids whose parents are away for the week decide to chloroform and tie up their virginal babysitter. What starts as a frivolous game turns serious when the kids invite three friends over to view their handiwork. Overwhelmed by their newfound freedom from adult supervision, these five psychopaths-in-training decide to prolong their “game.” Before it’s all done the 20-year old heroine will have been driven mad, raped, tortured in unspeakable ways and eventually murdered. Ditto a homeless man who has the misfortune to be in the area at the wrong time.

The above may sound exploitive, and possibly even darkly comedic (you may recall a similar captive babysitter premise from an I LOVE LUCY episode), but Johnson is dead serious in his exploration of pubescent sociopathology. In agonizingly drawn-out, minutely detailed prose he describes step by step the story’s hideous events and, more importantly, the mental states leading up to them. The kids’ various psychologies are carefully depicted with utter conviction; psychological jargon was quite prevalent (often irritatingly so) in seventies-era fiction, but this novel, unlike so many others of the time, has a resonance that if anything is amplified in post-Columbine America. Be forewarned, though: it never flinches or plays it safe, with a horrifying climax that wasn’t as hideous as I expected—it was actually worse!

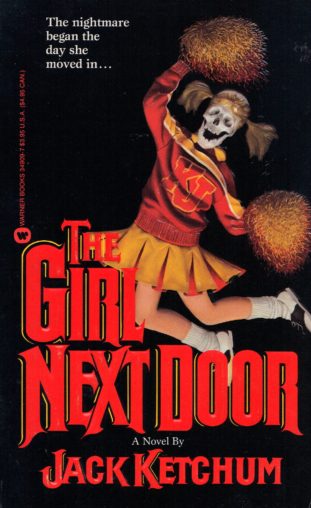

Finally we have THE GIRL NEXT DOOR by Jack Ketchum. It’s the most widely known of the novels discussed here, having been adapted into a potent 2007 film. Reading it around the time of its initial 1989 publication (bearing one of the most outrageously misleading covers of all time) I figured this wrenching novel represented the outer reaches of fictional extremity. Needless to add, I hadn’t yet read LET’S GO PLAY AT THE ADAMS’ or THE MARTYR, in whose company THE GIRL NEXT DOOR seems downright kind-hearted.

Finally we have THE GIRL NEXT DOOR by Jack Ketchum. It’s the most widely known of the novels discussed here, having been adapted into a potent 2007 film. Reading it around the time of its initial 1989 publication (bearing one of the most outrageously misleading covers of all time) I figured this wrenching novel represented the outer reaches of fictional extremity. Needless to add, I hadn’t yet read LET’S GO PLAY AT THE ADAMS’ or THE MARTYR, in whose company THE GIRL NEXT DOOR seems downright kind-hearted.

Ketchum retains many of the particulars of the Sylvia Likens case but adds a pivotal character: the youthful narrator David, who lives next door to Meg, the tortured girl. He’s witness to the many heinous acts inflicted on Meg and even, despite his revulsion, complicit in them. After all, David out of all the characters seems to possess a fully functioning moral compass and knows what’s happening is wrong, but by the time he gets around to actually taking action it’s far too late.

As a gross-out spectacle THE GIRL NEXT DOOR outdoes most splatterpunk fiction with its many traumatizing acts of aggression and sadism. Equally potent is Ketchum’s ingenious plotting, which accomplishes the difficult feat of shifting from a nostalgic reminiscence (the first hundred or so pages contain very little that’s overtly horrific) to an almost unbearably intense horror fest without feeling the slightest bit jarring or unbalanced.

The characterizations are also flawlessly achieved. The people in this book are so vividly conveyed that their actions never feel at all unconvincing, particularly in the case of Ruth, the mentally disturbed ringleader of the madness. So palpable is Ruth’s evil that more than once I wanted to reach through the pages and strangle the life out of her, but, even more disturbingly, there were times when I actually found myself sympathizing with her. Few novels of any kind could pull off such a seemingly inexplicable dichotomy, but THE GIRL NEXT DOOR does, and with stunning finesse.

So there you have it: three virtuoso explorations of madness and murder that are guaranteed to leave a mark. THE MARTYR, LET’S GO PLAY AT THE ADAMS’ and THE GIRL NEXT DOOR all deserve—nay, demand—to be experienced by receptive readers, although I’d strongly advise against reading them back-to-back, as, in all seriousness, I believe doing so could cause irreversible brain damage!