Assembling a best-books-of-the-year list is always a dicey proposition. Quite simply, nobody can be expected to track down and read every worthwhile book printed over the course of the previous year, especially one who goes out of his way to track down the year’s more obscure, esoteric publications. Still, in compiling the following list I feel I’ve come up with a number of interesting books that you won’t find in too many other such rankings. This means no Stephen King offerings (or even those of his son Joe Hill), although I did include a Clive Barker novel—which leads up to my first category…

FICTION

That Clive Barker novel is CLIVE BARKER’S NEXT TESTAMENT, a novelization of the 2013 comic book miniseries scripted by Barker and MARK ALAN MILLER. This novel, released in limited edition hardcover format by Earthling Publications, was written by Miller, although Barker’s touch is evident in the conception, if not the prose. The prose, in fact, is one of NEXT TESTAMENT’S weaker elements, being somewhat pedestrian in comparison to the rich and baroque vernacular we’ve come to expect from Clive Barker.

That Clive Barker novel is CLIVE BARKER’S NEXT TESTAMENT, a novelization of the 2013 comic book miniseries scripted by Barker and MARK ALAN MILLER. This novel, released in limited edition hardcover format by Earthling Publications, was written by Miller, although Barker’s touch is evident in the conception, if not the prose. The prose, in fact, is one of NEXT TESTAMENT’S weaker elements, being somewhat pedestrian in comparison to the rich and baroque vernacular we’ve come to expect from Clive Barker.

The narrative, though, definitely evinces Barker’s fingerprints, from the opening passages onward. That opening features the sixty year old Julian Demond unearthing a multi-hued being known as Wick. This personage is, in fact, God—the vengeful God of the Old Testament, to be precise, who performs miracles that invariably involve mass destruction and violent death. Arrayed against Wick and Julian are Wick’s hipster son Tristan and his fiancée Elspeth, both of whom are, frankly, quite boring—thus bringing up a major flaw in Clive Barker’s oeuvre: his monsters are invariably far more interesting than the human characters we’re supposed to be rooting for.

But NEXT TESTMENT is a terrific read nonetheless, being laudably audacious and provocative, and bearing an agreeably apocalyptic arc. Plus, the prose, even if it isn’t entirely Clive Barker worthy, is impressively crisp and descriptive, effectively transposing the artwork of the comic (which, for the record, I haven’t read in its entirety) to the printed page.

Another novel by a prominent genre scribe that debuted in 2017 was LITTLE HEAVEN by NICK CUTTER (Gallery Books), following up his wrenching debut novel THE TROOP and its not-as-good follow-up THE DEEP. LITTLE HEAVEN falls somewhere between those two poles; certainly it contains all of Cutter’s attributes, including solid characterizations and a facility for the grotesque that borders on genius, but it suffers from an unwieldy structure.

The IT-like narrative focuses on three mercenaries and a shape-shifting something loose in the deserts of New Mexico. The majority of the text takes place in the late 1960s, with the protagonists drawn to a settlement known as Little Heaven. This “Heaven” is home to a nutty religious cult presided over by a lunatic who preaches a dark, apocalyptic brand of Christianity. The shape-shifting critter is lurking nearby, and, needless to add, transforms Little Heaven into a far more forbidding environ; the three protagonists come away having made wishes that are granted by the critter, in not-always-welcome ways.

I say the whole thing is too long and overcomplicated, lacking the leanness and concentration of THE TROOP. Another problem is with the many derivative elements, such as a creepy monster kid appearing at a window and exhorting a friend to let him in (a blatant lift from SALEM’S LOT), and also the descriptions of the shape-shifter’s ever-mutating appearance (which are right out of THE THING). On the plus side is the author’s gruesome invention, which results in some memorable set-pieces involving bloodletting, physical mutation and insects a ’plenty. It’s just too bad those elements are spread out over a severely protracted canvas whose bloat lessens their impact.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY is among my favorite writer/filmmakers, and he was represented in 2017 by the film ENDLESS POETRY (my  thoughts on which can be found here) and also the Humanoids published young adult graphic novel THE MAGICAL TWINS, scripted by Jod and illustrated by GEORGES BESS (whose artwork previously graced the Jodorowsky scripted volumes SON OF THE GUN and THE WHITE LAMA). As we’d expect from this pair, THE MAGICAL TWINS is an extravagant concoction with enough color and imagination to fill multiple science fiction trilogies.

thoughts on which can be found here) and also the Humanoids published young adult graphic novel THE MAGICAL TWINS, scripted by Jod and illustrated by GEORGES BESS (whose artwork previously graced the Jodorowsky scripted volumes SON OF THE GUN and THE WHITE LAMA). As we’d expect from this pair, THE MAGICAL TWINS is an extravagant concoction with enough color and imagination to fill multiple science fiction trilogies.

The setting is a magical netherworld in which a twin brother and sister embark on a quest to rescue their father from the clutches of Tartarath, the ruler of the kingdom of darkness. The twins bring along a dragon-bird companion named Lyrena but are forbidden from riding him, and advised to make extensive use of their five senses. Among the marvels the twins encounter on their journey are a giant land-dwelling octopus, a massive disembodied brain, an erupting volcano, an island made entirely of candy, a building held up by demon-infested columns and the scary Tartarath himself.

It’s all presented in an oversized hardcover format, which does Bess’s dense, layered imagery justice. Jodorowsky’s script admittedly isn’t always up to snuff, insisting on having its characters frequently explain self-evident images (as when the protagonists are shown standing at the edge of a pond, accompanied by the words “Look, a pond!”), apparently for the edification of its target audience. That audience is also given a moral in the final pages, and a contrived happy ending (although the distinctly phallic imagery that features in much of the book didn’t seem too kid friendly to me). Again, though, it’s the extravagance, imagination and gorgeous artwork that make THE MAGICAL TWINS the memorable tome it is.

The Other Press published English translation of PHILIPPE DJIAN’S ELLE is, I’d argue, the sole major benefit of director Paul Verhoeven’s renowned 2015 film adaptation (about which I’m lukewarm). Like the film, the novel is a “thriller” of sorts about a rape and its aftermath. The perpetrator of said rape is an unidentified masked male and his victim is Michele, a middle-aged film executive who narrates the book. Her reaction to the rape is complicated, to say the least. Likewise her relationships with her elderly mother and twentyish son, both of whom Michele supports financially.

This is one of the few truly convincing examples of a woman’s voice rendered by a member of the opposite sex. That’s a damn good thing, as the portrayal of Michele could have very easily turned into a misogynistic caricature given her actions over the course of the book. Some will say (and have said) that’s the case anyway, but Michele’s attitudes and behavior are consistent throughout—which is to say consistently unpredictable.

Reviewers have described Michele’s relationship with her rapist as a “cat and mouse” dynamic, but that’s not an accurate description. In fact, the rapport that develops between the two characters is difficult to properly define, being morally complex and politically incorrect. I’ll refrain from revealing the hows and whys of that dynamic, as the novel’s unpredictability is one of its primary strengths. As translated by Michael Katims, ELLE is an extremely compelling, if not especially pleasant or comforting, novel that reeks of harsh reality.

THE TWENTY DAYS OF TURIN by GIORGIO DE MARIA (W.W. Norton & Co.) is the first-ever English version of a novel that was initially published in Italian back in 1977. THE TWENTY DAYS OF TURIN is an enduring cult classic in its native land, and in recent years has come back into prominence due to the fact it inadvertently predicted the rise of the internet and, more specifically, social media.

THE TWENTY DAYS OF TURIN by GIORGIO DE MARIA (W.W. Norton & Co.) is the first-ever English version of a novel that was initially published in Italian back in 1977. THE TWENTY DAYS OF TURIN is an enduring cult classic in its native land, and in recent years has come back into prominence due to the fact it inadvertently predicted the rise of the internet and, more specifically, social media.

That latter aspect is evident in the novel’s driving element: the Library, a vast storehouse of journals written by various individuals residing in Turin, Italy. The Library was intended as a therapeutic endeavor allowing socially maladjusted folk to connect with each other anonymously (sound familiar?), but it resulted in widespread fear and paranoia, and appears to have some bearing on a series of unsolved murders plaguing the city.

The constant apprehension that pervades the narrative, and the shadowy killings, were apparently quite evocative of the terrorist activity rampant in Italy during the 1970s. This means that if TWENTY DAYS OF TURIN can be said to have an overriding flaw it’s that it dramatizes an extremely specific time and place that, despite the contemporary resonance, feels quite removed from our own.

A further complaint is with the ending, in which the author goes full-tilt surreal. Nothing is really explained, much less resolved, which is fine in a Robert Aickman story, but not in a carefully hewn mystery narrative like the one presented in these pages.

And with that, we’ll move onto my next category…

NON-FICTION

First up in this category is DIRECTOR’S CUT (ECW Press), which isn’t the greatest movie director memoir I’ve ever read, but a vital one nonetheless. Why? Because its author, the 85 year old TED KOTCHEFF, has had an amazingly varied and eventful career, with a filmography that includes the bleak Australian thriller WAKE IN FRIGHT, the Canadian dramedy THE APPRENTICESHIP OF DUDDY KRAVITZ and the Hollyweird products FUN WITH DICK AND JANE, FIRST BLOOD and WEEKEND AT BERNIE’S.

Kotcheff’s start in the industry, he claims, was via the Canadian Broadcasting Company at age 24. Working in Hollywood was impossible due to Kotcheff being falsely branded a communist by the U.S. Justice Department at age 22—the reason he travelled to Australia to make WAKE IN FRIGHT. Kotcheff did eventually get to work in the U.S. after scoring an international success with DUDDY KRAVITZ in 1974, which led to FUN WITH DICK AND JANE and the Nick Nolte football drama NORTH DALLAS FORTY. Next came WHO IS KILLING THE GREAT CHEFS OF EUROPE? and FIRST BLOOD, followed by UNCOMMON VALOR, WEEKEND AT BERNIE’S and the creation of LAW AND ORDER SVU.

Many juicy anecdotes are included in Kotcheff’s recollections, such as his misadventures in the Australian outback during the production of WAKE IN FRIGHT and the claim that Kathleen Turner was difficult (not hard to believe!) on the set of Kotcheff’s failed 1988 comedy SWITCHING CHANNELS. For the most part, however, Kotcheff is quite generous toward his collaborators—even the legendarily irascible Gene Hackman is praised—making for a pleasant read by an evidently pleasant man.

MILLER AND MAX by LUKE BUCKMASTER (Hardie Grant Books) is an absolute must for MAD MAX fans, a sort-of biography of Australian  filmmaker George Miller and his signature creation. The book could be a bit deeper on the whole, but delivers what it promises: a fast-moving and entertaining study worthy of the films of its subject, a warm and genial man who’s known for directing four of the most violent and kinetic movies all time.

filmmaker George Miller and his signature creation. The book could be a bit deeper on the whole, but delivers what it promises: a fast-moving and entertaining study worthy of the films of its subject, a warm and genial man who’s known for directing four of the most violent and kinetic movies all time.

The book begins with a description of Miller’s upbringing in the rural Queensland community of Chinchilla, and his years attending medical school at the University of New South Wales. During that time he met Byron Kennedy, his future producing partner, in a film workshop. From that meeting emerged the ultra-low budget MAD MAX, a massive hit that for years held the title of the most profitable movie of all time.

A sequel was inevitable, and arrived in the form of 1981’s MAD MAX 2/THE ROAD WARRIOR. Its production was a much smoother one than that of its predecessor, although the filming of Max’s third incarnation, 1985’s MAD MAX BEYOND THUNDERDOME, was something of a nightmare. An interval of nearly thirty years preceded Max’s next adventure, the mega-budgeted MAD MAX: FURY ROAD. Its shoot involved more trouble, in the form of years of development hell and inhospitable desert locations in Namibia, yet it all came together in a film that, unexpectedly enough, was a multiple Oscar winner.

About George Miller’s non-MAD MAX affiliated films (which include THE WITCHES OF EASTWICK, LORENZO’S OIL and BABE: PIG IN THE CITY) little is said. But then, the title makes it clear that the author’s focus is on Mad Max, in which respect MILLER AND MAX more than succeeds.

OFF THE CLIFF by BECKY AIKMAN (Penguin Press) explores the production of 1991’s feminist-minded classic THELMA AND LOUISE. The book commences with the writing of the screenplay by Callie Khouri, a disgruntled music video production manager who vented her frustration in the script. It passed into the hands of Ridley Scott, whose initial plan was only to produce, yet he ended up directing the modestly budgeted shoot that took place largely in California and Utah.

Author Becky Aikman does a good job keeping the details of that shoot lively and readable, despite the fact that it was notably uneventful and conflict-free. Those things, however, were definitely not true of THELMA AND LOUISE’S reception, which was quite fraught in every respect, with innumerable outraged newspaper and magazine editorials devoted to it (a big deal in the pre-social media age). One thing that is for sure is the fact that, as described here, this production, which features complicated heroines who eventually commit suicide, is one that could never happen in today’s risk-averse Hollywood.

Perhaps the most interesting portions of the book were the final pages, in which the legacy of THELMA AND LOUISE is explored—or better yet, the non-legacy, as the feminist revolution it was credited with starting never occurred (thus explaining in part why I’m so skeptical of the woman-friendly “Sea Change” America is supposed to be currently undergoing).

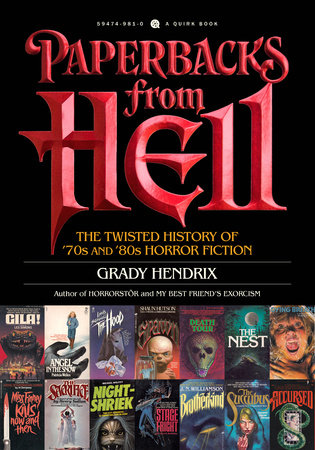

PAPERBACKS FROM HELL: THE TWISTED HISTORY OF ‘70s and ‘80s HORROR FICTION by GRADY HENDRIX (Quirk Books) explores a subject I know a bit about: paperback horror novels of the so-called “horror boom” of the 1970s and 80s. I’m obviously a receptive reader, and unless the author really screws things up I can’t fathom not enjoying the book—and the author, thankfully, doesn’t screw things up (much). Some readers will doubtless criticize the jokey, smart-assed prose, but I say it’s appropriate.

PAPERBACKS FROM HELL: THE TWISTED HISTORY OF ‘70s and ‘80s HORROR FICTION by GRADY HENDRIX (Quirk Books) explores a subject I know a bit about: paperback horror novels of the so-called “horror boom” of the 1970s and 80s. I’m obviously a receptive reader, and unless the author really screws things up I can’t fathom not enjoying the book—and the author, thankfully, doesn’t screw things up (much). Some readers will doubtless criticize the jokey, smart-assed prose, but I say it’s appropriate.

Hendrix provides a more-or-less chronological recounting of the horror boom, from its late 1960s inception to its early 1990s demise. Innumerable novels are mentioned, ranging from standbys like THE EXORCIST, SALEM’S LOT and FALLING ANGEL to the comparatively obscure, but equally potent, likes of LET’S GO PLAY AT THE ADAMS’ by Mendal Johnson, THE HAPPY MAN by Eric C. Higgs and the novels of the late Ken Greenhall.

For the sociologically minded among you there’s info about the real-life upheavals that powered those novels, such as the “white flight” of the seventies (hence the glut of haunted house books that appeared then) and the satanic panic of the eighties (manifested in the gleefully amoral splatterpunk fiction of the era). Also included are profiles of many of the artists who created the unforgettable covers of these novels.

I could into detail about the many vital books left out of PAPERBACKS FROM HELL, but will stop here. After all, to fully do justice to this subject would require a span at least three times that of PAPERBACKS FROM HELL’S 256 page length, and I think most readers will be pleased with what’s here.

I’ll conclude this section with what was my favorite book, fiction or non, of 2017. That would be A LIT FUSE: THE PROVOCATIVE LIFE OF HARLAN ELLISON by NAT SEGALOFF (NESFA Press), an excellent biography of an individual who should need no introduction. If you’re a horror/fantasy/science fiction buff you’re probably familiar with at least some of the writings of Harlan Ellison, which include books like I HAVE NO MOUTH AND I MUST SCREAM and MEFISTO IN ONYX, and innumerable stories, essays, lectures, etc. I’m sure you’re also familiar with the many stories about him, which are as outlandish as his fiction.

Author Nat Segaloff does a good job tracing Ellison’s outrages, which began during his childhood in Painsville, OH in the late 1930s and 40s. About those years Ellison admits “I was a nuisance, I was a pain in the ass, I was a real fuckin’ nightmare.” From there Ellison worked a variety of odd jobs before finding his calling as a writer, primarily in the print and television mediums. Along the way he made a lot of enemies with his naturally combative, egomaniacal personality, and married no less than five times.

As any sympathetic Ellison biographer inevitably must, Segaloff functions more often than not as an apologist for his subject. Innumerable excuses are made for Ellison’s behavior, but Segaloff doesn’t shy away from his subject’s darker side. Examples of this range from the legendary mailing-a-dead-rodent-to-a-publisher account to demanding Denis Kitchen of Kitchen Sink Press put Ellison on his comp list, and then bitching that the free stuff he received wasn’t top quality.

The book ends on a sad note, with Ellison felled by a debilitating 2014 stroke. I may be projecting, but I detected a hint of glee in the climactic line “For years he had fought the entire world. Now he was fighting himself.”

Moving on to category number three…

REPRINTS

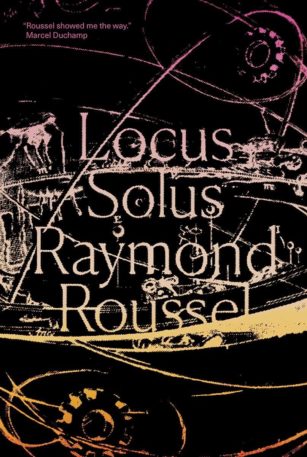

Foremost among the many worthwhile publications from past decades that were reprinted in 2017 was a book I never thought I’d see in readily available format in America: LOCUS SOLUS by RAYMOND ROUSSEL, initially published in French back in 1914, and newly translated by Rupert Copeland Cunningham (and published by New Directions). Roussel’s previous novel IMPRESSIONS OF AFRICA remains one of the most astonishing displays of unfettered imagination I’ve ever experienced, and LOCUS SOLUS matches it.

available format in America: LOCUS SOLUS by RAYMOND ROUSSEL, initially published in French back in 1914, and newly translated by Rupert Copeland Cunningham (and published by New Directions). Roussel’s previous novel IMPRESSIONS OF AFRICA remains one of the most astonishing displays of unfettered imagination I’ve ever experienced, and LOCUS SOLUS matches it.

It’s about a walk through a rich scientist’s wonderful garden, which features a wealth of incredible exhibits. The marvels on display include a tool with a mechanical hand that creates a vast mosaic of human teeth; a gargantuan aquarium filled with breathable water wherein the decomposing head of Danton is inspired by a skinned cat with a bullhorn to recite famous speeches; a giant glass cage housing several corpses under the influence of a drug that allows them to relive important episodes from their lives; a chicken with a growth in its throat causing it to spit blood in the form of words; and so on.

As in IMPRESSIONS OF AFRICA Roussel describes these marvels and then gives us lengthier passages detailing their back stories, which are often more outlandish than the resulting exhibits. The writing is disarmingly controlled and straightforward (based on eccentric principles of wordplay that don’t quite register in the English translation), yet the subject matter, particularly in the section with the reanimated corpses, is often unbearably emotional. I think it’s safe to say that nobody else wrote anything remotely like this delirious celebration of irrationality and imagination; it remains one of the few books that are truly indispensable, whether you know about it or not.

Nearly as potent in the category of surreal literature is DOWN BELOW by LEONORA CARRINGTON, which likewise appeared in a new edition in 2017 (from NYRB Classics). This short novel is something of a change of pace from the type of mythologically-informed surreal fiction in which Carrington specialized (collected in THE COMPLETE STORIES OF LEONORA CARRINGTON, which also appeared in 2017), but only slightly, being the true story of Carrington’s descent into madness and her incarceration in a mental hospital.

Although the events it describes all apparently happened, DOWN BELOW reads like a surrealist nightmare, being a deeply hallucinatory barrage of horrific visions. It’s often difficult to sort out the “real” from the unreal (which is most likely the whole point), and this often makes for a reading experience that’s downright irritating. I wouldn’t have missed this book for anything, though, as it makes for an excellent companion piece to better known mental illness themed narratives like Sylvia Plath’s THE BELL JAR and (especially) Anna Kavan’s ASYLUM PIECE.

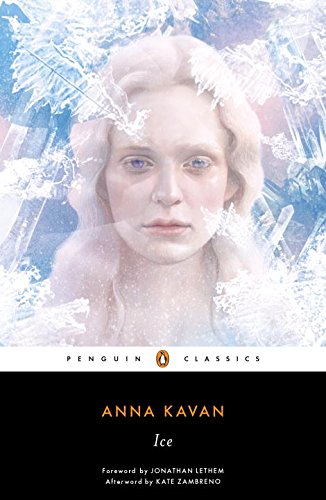

Speaking of ANNA KAVAN, her masterpiece ICE was republished, on its fiftieth anniversary, by Penguin Classics, complete with a newly written forward by Jonathan Letham. It’s one of my favorite sci-fi novels, and certainly one of the strangest such novels I’ve ever read.

Speaking of ANNA KAVAN, her masterpiece ICE was republished, on its fiftieth anniversary, by Penguin Classics, complete with a newly written forward by Jonathan Letham. It’s one of my favorite sci-fi novels, and certainly one of the strangest such novels I’ve ever read.

Anna Kavan spent a large part of her life in mental institutions, and eventually died from a heroin overdose (not long, in fact, after ICE was published). Her novels and stories are all, first and foremost, extremely depressing, and ICE is no different, being set in a world threatened by drifting icebergs. In the chaos that inevitably ensues our few-bricks-shy-a-load protagonist pursues “the Girl” (nobody has any names in this book) through an unidentified country. Neither he nor we are entirely sure why this guy is doing what he does, but then it’s clear from the start that his grip on reality is tenuous at best.

A FIGHT CLUB-like twist at the end partially clears things up, but the hallucinatory atmosphere conjured by Kavan remains peerlessly mysterious. The ice has been likened by many commentators to the author’s drug addiction, and the sense of impending doom does indeed feel a bit too authentic for comfort: “A mirage-like arctic splendor towered all around, a weird, unearthly architecture of ice…we were trapped by those encircling walls, a ring of ghostly executioners, advancing slowly, inexorably to destroy us.”

We mustn’t forget KEN GREENHALL’S masterful HELL HOUND, originally published back in 1977, which made its long awaited reappearance in print forty years later, courtesy of Valancourt Books (who also provided new editions of Greenhall’s other novels ELIZABETH and CHILDGRAVE, both of which likewise come highly recommended). It’s a first class piece of work, an unsung classic of the bizarre that ranks with A CLOCKWORK ORANGE and THE WASP FACTORY.

It’s the story of Baxter, an ugly Bull Terrier who can think like a human—a deeply nasty, brutish and vindictive human. Baxter’s thoughts are imparted via short first person chapters in which he invariably laments his current situation and attempts to find a way out of it. Baxter initially finds himself in the care of a lonely old woman who nauseates him; he ends up giving the coot a deadly spill down the stairs in order to be with a young couple next door. Unfortunately the young wife is pregnant, which spoils things for Baxter. He commits murder again, drowning the child in a backyard pond, which does NOT have the desired effect. He winds up with a seriously deranged Hitler obsessed kid, one who likes to hang out in a junkyard where he’s created a mini-bunker in honor of his idol’s place of death. It seems that Baxter has at last found his ideal mate, but the boy and dog are a bit too much alike, leading to a violent showdown that only one of them will survive.

Around this twisted drama revolves a rich a gallery of supporting characters—the boys’ clueless parents, his sympathetic teacher, a young girl and her callous father, a decrepit old man—that comprise a superbly corrosive portrait of small-town America in a narrative that works as both an Orwellian satire of pet ownership and an old-fashioned parable about the wily nature of evil. It’s that rarity of rarities: a totally unique creation. I promise you’ll have a difficult time finding anything else quite like it!

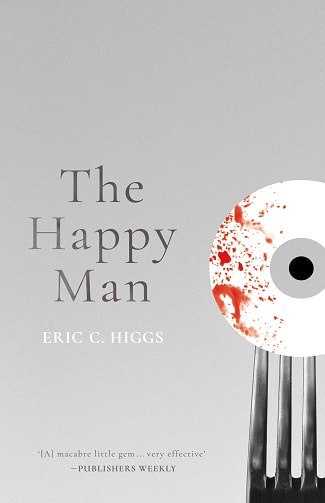

Another essential Valancourt Books reprint from 2017 was THE HAPPY MAN by ERIC C. HIGGS. Initially published (and largely ignored) back in 1985, it’s one of the great modern horror novels, a profoundly unsettling piece of work that explores untold depths of depravity in under 200 pages, and with a minimum of graphic detail.

in 1985, it’s one of the great modern horror novels, a profoundly unsettling piece of work that explores untold depths of depravity in under 200 pages, and with a minimum of graphic detail.

The setting is the backwoods around California’s Mexican border, near the suburb of Chula Vista (where, FYI, much of my family was once concentrated). It proves to be an extremely effective setting with its dusty hills and canyons, where Charles Ripley, the mild-mannered protagonist, becomes intrigued by a neighbor’s seemingly carefree lifestyle—and is inexorably drawn into a darkly seductive world of illicit sex, illegal drugs, casual murder and worse. It seems that the neighbor and his family are members of a shadowy group called “The Society of Friends,” whose adherents are required to loosen all their inhibitions. This Ripley does, in gradual and horrifically convincing fashion—the ultimate question, however, is how long he’ll be able to maintain his new-found moral vacuum, and what he’ll do when he regains his senses.

As I said, the book is fairly restrained in its presentation of physical grotesquerie, being a primarily psychological account. The narrative is lively and energetic throughout, with compact and descriptive prose that ensnares the reader in much the same manner as the protagonist—and then lets loose with an incredibly potent literary kick in the gut!

RED RANGE is a JOE R. LANSDALE authored, SAM GLANZMAN illustrated graphic novel, initially published (in black and white) in 1999. A “Weird Western,” RED RANGE has largely vanished from sight in the ensuing years, so this new edition from IDW, which comes with a newly written afterward by Stephen R. Bissette, is most welcome (and it’s in color!).

As both Klaw and Bissette make clear, RED RANGE seemed a bit excessive and out-of-place in 1999. This was because of its racial overtones, which are delineated in a decidedly blunt manner; check out the opening pages, depicting a black man getting mutilated in a truly horrific manner by Ku Kluxers. The lynchee is the father of young Turon, who is saved from perishing at the bottom of a well by an African American bandit known as The Red Mask, a.k.a. Caleb Range. There follows a relentless chase through the Texas wilderness, until a most unexpected twist places this unsparing saga in LAND OF THE LOST territory, complete with dinosaurs and a radical recalibration of the racial divide of the earlier pages.

There will be (and have been) those who claim the incendiary nastiness of RED RANGE’S early pages doesn’t jibe with the loopy fantasy of the later ones, and they won’t be entirely off-point. But I quite enjoyed the joyous collision of tones and genres, a trademark of the fiction of Joe Lansdale, who was at his wildest here. And we mustn’t forget the artwork of Sam Glanzman, a veteran comic book artist who’s been around since the 1940s. His art in RED RANGE is appropriately tough and hard-bitten, yet doesn’t shy away from giving us a good view of the fantasy elements that come to dominate the proceedings.

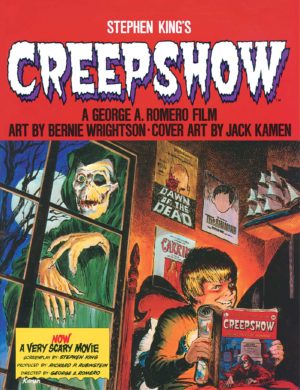

Onto the STEPHEN KING scripted, BERNIE WRIGHTSON illustrated CREEPSHOW, a most welcome reprinting of what until 2017 was one of King’s scarcest books. It’s the graphic novel adaptation of the five part anthology flick CREEPSHOW, and even if you don’t like the movie this book is a must-own, due to the artwork of the great Bernie Wrightson. CREESHOW contains some of Wrightson’s finest work, set down in a very old school layout that was wisely preserved in this reprint edition (meaning Gallery 13 wisely bypassed the “digital enhancement” comic book reprint craze).

Onto the STEPHEN KING scripted, BERNIE WRIGHTSON illustrated CREEPSHOW, a most welcome reprinting of what until 2017 was one of King’s scarcest books. It’s the graphic novel adaptation of the five part anthology flick CREEPSHOW, and even if you don’t like the movie this book is a must-own, due to the artwork of the great Bernie Wrightson. CREESHOW contains some of Wrightson’s finest work, set down in a very old school layout that was wisely preserved in this reprint edition (meaning Gallery 13 wisely bypassed the “digital enhancement” comic book reprint craze).

The first story is “Father’s Day,” about a murdered man’s beyond-the-grave revenge on his murderous widow. It’s followed by “The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill,” a “Colour Out of Space” inspired account of a hick turned into a fungoid monster by a meteorite that unleashes a deadly contagion. “The Crate” involves an old crate containing a hungry man-eating something and a janitor’s ultra-bitchy wife, while in “Something to Tide You Over” a jealous husband murders his philandering wife and her lover in macabre fashion, only to have the tables turned on him. Finally, in “They’re Creeping Up On You,” a rich hypochondriac gets his comeuppance in the form of a mass of cockroaches.

If there’s a weak link here it would be the script by Stephen King, which is marked by great conceptions and not-so-great conclusions. Again, though, it’s not the scripting that makes CREEPSHOW the vital book it is but the artwork, in which area it simply cannot be faulted.

And now it’s time for the fourth portion of this survey, a “catch-up” category entitled…

2016 BOOKS I INITIALLY MISSED

First up in this category is 70s MONSTER MEMORIES, edited by ERIC McNAUGHTON (Buzzy Krotic Productions). A limited edition UK-only publication, 70s MONSTER MEMORIES is about genre movies of the 1970s, as remembered by the (mostly British) “Monster Kids” who came of age in that era. Nearly every conceivable facet of 1970s monster movie lore is covered: horror movie magazines and reference books, model kits, action figures, posters, trading cards, TV movies, soundtrack albums, comics, etc. Also included are an excellent selection of photographic illustrations that complement the text quite nicely.

Given the wide range of authors and subject matter, certain chapters are obviously better than others. An interview with a Famous Monsters cover artist is marred by the fact that the interviewer does the majority of the talking, while a piece entitled “LA CABINA: Allegory of An Era,” woefully lacks the nostalgic angle that characterizes most of the rest of the contents. But those things don’t lessen the book’s cumulative effect, which is, as promised, pleasantly nostalgic. There are even some attempts to examine the roots of that nostalgia, as in an interview with toy collector extraordinaire Dave Swift, who admits to desiring a direct connection to a time when his life was much easier, which makes for a reading experience that provides some real insight amid all the retro fun.

One of the most unexpected surprises of 2016 was the Tor published HEX by THOMAS OLDE HEUVELT, an altogether odd and unpredictable horror thriller from the Netherlands. Its setting is Black Spring, an upstate New York town haunted by the specter of Katherine van Wyler, who back in the 17th Century was executed in the land that became Black Spring—where her ghost, appearing as the old woman she was with her eyes and mouth sewn shut, has remained ever since.

Hex, a high-tech control center, has been set up to monitor Katherine’s doings. Hex also functions as Black Spring’s very own Big Brother, keeping tabs on its citizenry and making sure they stay within the town limits. But a group of troublemaking teenagers, understandably dissatisfied with the cloistered existence forced on them by Hex, decide to rebel. This has the effect of making Black Spring’s connections with its less enlightened past horrifyingly apparent, resulting in a toxic atmosphere of suspicion and persecution. Worst of all, Katherine’s spirit becomes quite agitated, and grows more actively involved with the flesh-and-blood people among whom she walks…

The novel is quite absorbing despite the fact that its American setting is never entirely convincing. The disarmingly matter-of-fact manner in which the people of Black Spring deal with the ghostly presence in their midst is, as the author admits in a nonfiction afterward, a very Dutch attribute. But HEX is one of the few recent novels that succeeds in effectively marrying ancient superstition and modern technology. It’s good enough, in fact, that I’m nearly tempted to excuse the novel’s most grievous flaw: the fact that it, like so many other modern horror novels, is around 100 pages too long!

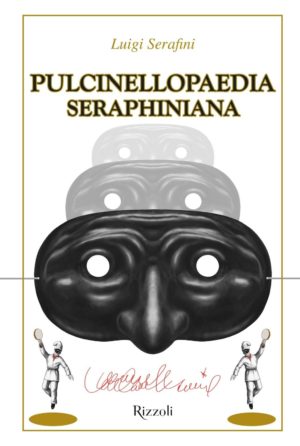

Another vital 2016 publication was Italian illustrator LUIGI SERAFINI’s heretofore impossible-to-find 1984 follow-up to his wordless wonder  CODEX SERAPHINIANUS: PULCINELLOPAEDIA SERAPHINIANA, which was given a most welcome reprinting by Rizzoli. CODEX SERAPHINIANUS is often described as the strangest book ever published, and PULCINELLOPAEDIA is nearly as bizarre, being a collection of wordless images centered on the figure of Pulcinella (known to English speakers as Punch, of Punch and Judy infamy), a staple of the 17th Century commedia dell-arte who remains iconic in Europe. Here in the US that’s not the case, which explains why this volume never caught on here like CODEX did. It is nonetheless a gorgeously drafted oddity that like its predecessor exerts a near-otherworldly fascination.

CODEX SERAPHINIANUS: PULCINELLOPAEDIA SERAPHINIANA, which was given a most welcome reprinting by Rizzoli. CODEX SERAPHINIANUS is often described as the strangest book ever published, and PULCINELLOPAEDIA is nearly as bizarre, being a collection of wordless images centered on the figure of Pulcinella (known to English speakers as Punch, of Punch and Judy infamy), a staple of the 17th Century commedia dell-arte who remains iconic in Europe. Here in the US that’s not the case, which explains why this volume never caught on here like CODEX did. It is nonetheless a gorgeously drafted oddity that like its predecessor exerts a near-otherworldly fascination.

It begins with Pulcinella, with his iconic big nosed mask, being birthed from a large breast-like structure. The rest of the book consists of impressionistic depictions of Pulcinella in various guises and forms (such as the top of an umbrella and the tips of shoes). The imagery is often downright grotesque, as in a depiction of Pulcinella’s hands transformed into distinctly testicular plates of spaghetti, and another of him literally excreting people, who upon hitting the ground multiply exponentially. It’s all marked by Serafini’s illustrative genius, evinced by gorgeously detailed black and white drawings with splashes of red. I won’t pretend to understand what any of it means, as in Serafini’s bizarre universe puzzlement is a key component.

That’s it! But before going I’ll provide a few brief looks at upcoming publications that look promising…

LOOKING FORWARD

ALL I EVER DREAMED by MICHAEL BLUMLEIN

Another Valancourt Books release, one that promises to collect all the short fiction written by the great (and shamefully neglected) Michael Blumlein.

AN AMERICAN STORY by CHRISTOPHER PRIEST

The specter of 9/11 is said to drive this novel, a contemporary fantasy by England’s talented Christopher Priest, who describes it as “being on the speculative end of the spectrum of fantastic literature.”

BLOOD’S A ROVER by HARLAN ELLISON

It’s taken some time, but it seems that in 2018 we’ll at last be getting the complete saga of Vic and Blood (of A BOY AND HIS DOG fame) by Harlan Ellison, which has been in the works for seemingly ever.

THE HOWLING: STUDIES IN THE HORROR FILM by LEE GAMBIN

No, I was never a huge fan of the THE HOWLING, but I do like the Centipede Press published STUDIES IN THE HORROR FILM series enormously, and so am looking forward to this publication in spite of myself.

THE HUNGER by ALMA KATSU

The tragic story of the Donner Party (which, as you may recall, involved cannibalism) is given a supernatural rethink in this novel, which has already been sold to the movies.

THE LISTENER by ROBERT McCAMMON

From the talented Robert McCammon, a supernaturally-tinged kidnapping thriller that’s set during the Great Depression. I’m intrigued!

MOON FACE by ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY, FRANCOIS BOUCQ

A graphic novel, scripted by the incomparable Alejandro Jodorowsky and illustrated by Francois Boucq, that promises an “uplifting and surreal satirical tale of strange magic and revolutionary freedom.”

THE PREPPER ROOM by KAREN DUVE

A Dedalus published German translation that’s been described thusly: “A hugely entertaining novel about feminism, masculinity and the battle between the sexes for domination which is full of grotesque humor and highly-charged eroticism.”

THE ROCKING-HORSE WINNER by D.H. LAWRENCE

A collection of supernatural tales by D.H. Lawrence that’s set to be given the deluxe Centipede Press treatment. I say it’s worth it for the amazing title story alone.

SIDE LIFE by STEVE TOUTONGHI

Paranoid Philip K. Dick inspired sci-fi that, based on the plot synopses I’ve read, looks extremely promising.