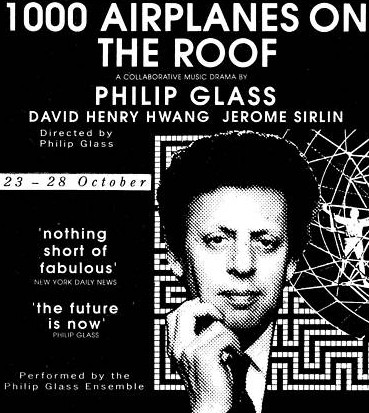

1000 AIRPLANES ON THE ROOF was a multi-media stage drama scripted by David Henry Hwang, designed by Jerome Sirlin and scored by Philip Glass. It’s been described as “part Freud, part Kafka and part Steven Spielberg,” being a deeply hallucinatory, psychologically centered account of an (apparent) alien invasion. Having seen it performed (twice!) at West L.A.’s Wadsworth Theater back in October of 1988, I can report that the show was a remarkable, mind-bending experience that, with its rollicking electronic score, ingeniously designed holographic scenery and artfully drafted script, showcased its three creators at the top of their respective forms.

1000 AIRPLANES ON THE ROOF was a multi-media stage drama scripted by David Henry Hwang, designed by Jerome Sirlin and scored by Philip Glass. It’s been described as “part Freud, part Kafka and part Steven Spielberg,” being a deeply hallucinatory, psychologically centered account of an (apparent) alien invasion. Having seen it performed (twice!) at West L.A.’s Wadsworth Theater back in October of 1988, I can report that the show was a remarkable, mind-bending experience that, with its rollicking electronic score, ingeniously designed holographic scenery and artfully drafted script, showcased its three creators at the top of their respective forms.

As written by M. BUTTERFLY’S David Henry Hwang, 1000 AIRPLANES ON THE ROOF takes the form of an extended monologue by “M,” a New Yorker who finds his reality dissolving. Among other things, M suffers hallucinations in which he sees his apartment building disappear and feels an object inserted into his right nostril, while an alien voice resounds in his head, warning him that “It is pointless to remember. No one will believe you. You will have spoken a heresy. You will be outcast.”

M doesn’t heed the voice, reaching back into his memories to re-experience a close encounter with inter-dimensional aliens that took place years earlier, amid a beehive in a rural farmhouse where M grew up. The “reality” of this encounter is never resolved, with the possibility broached that M might simply be a few bricks shy a load, a conclusion Sirlin’s profoundly surreal big city backdrops would seem to support. If the show can be said to have an underlying theme, it would likely be the insanity-inducing effects of urban living; as M ultimately concludes, “I had a bad day. I was confused because I once lived on a farm. But, no longer.”

In place of the expected sci fi pulpiness, Hwang’s text offers a highly immersive depiction of a mental breakdown, marked by uncertainty, apprehension and some genuinely haunting turns of phrase (“The room is saturated with the presence of things hidden”). It’s not unlike a more hallucinogenic take on Whitley Strieber’s COMMUNION, albeit one that’s unafraid to call itself fiction.

apprehension and some genuinely haunting turns of phrase (“The room is saturated with the presence of things hidden”). It’s not unlike a more hallucinogenic take on Whitley Strieber’s COMMUNION, albeit one that’s unafraid to call itself fiction.

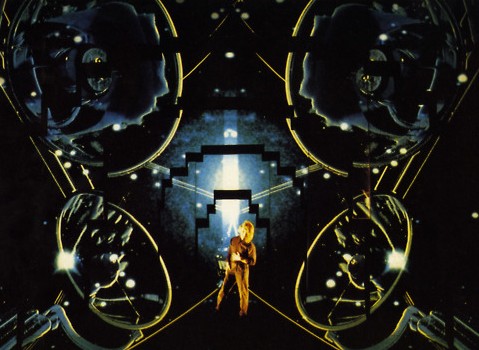

The scenery of Jerome Sirlin was instrumental in imparting that air of surreal apprehension. Sirlin, a longtime stage designer who’s worked on everything from Wagner’s Ring Cycle to a Madonna concert, provided an intricate series of screens upon which a variety of imagery was projected, including big city panoramas, faces and globular mosaics presented in fractured configurations that reflect the beehive imagery so integral to the text. The screens were staggered in a way that allowed the actor playing M (Patrick O’Connell and Jodi Long alternated) to directly interact with the scenery, most memorably in an early moment in which M appears to literally hop around the NYC skyline.

Then there’s the computerized music of Philip Glass. High-spirited, unapologetically cacophonous and largely free of the brooding minimalism that characterizes his most famous work (EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH, SATYAGRAHA, KOYAANISQATSI, etc.), it’s no surprise that many Glass fans have dismissed his 1000 AIRPLANES score. This Philip Glass buff, however, quite liked it (although I will admit the music sounded far better when played live than it does in cd/mp3 format), providing as it does a strong counterpoint to the oppressiveness of Hwang’s script. Furthermore, the score, despite its overall bounciness, contains passages that are as haunting and esoteric as nearly anything Glass has done (if nothing else, 1000 AIRPLANES certainly outdoes the other Philip Glass multi-media performances I’ve seen, which include a dance-heavy interpretation of Jean Cocteau’s LES ENFANTS TERRIBLES that clumsily overloaded a claustrophobic two character piece with over a dozen assorted performers, and a rescoring of Cocteau’s BEAUTY AND THE BEAST with live singers crooning the dialogue, which had the effect of making me long to see the film with its original soundtrack).

Then there’s the computerized music of Philip Glass. High-spirited, unapologetically cacophonous and largely free of the brooding minimalism that characterizes his most famous work (EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH, SATYAGRAHA, KOYAANISQATSI, etc.), it’s no surprise that many Glass fans have dismissed his 1000 AIRPLANES score. This Philip Glass buff, however, quite liked it (although I will admit the music sounded far better when played live than it does in cd/mp3 format), providing as it does a strong counterpoint to the oppressiveness of Hwang’s script. Furthermore, the score, despite its overall bounciness, contains passages that are as haunting and esoteric as nearly anything Glass has done (if nothing else, 1000 AIRPLANES certainly outdoes the other Philip Glass multi-media performances I’ve seen, which include a dance-heavy interpretation of Jean Cocteau’s LES ENFANTS TERRIBLES that clumsily overloaded a claustrophobic two character piece with over a dozen assorted performers, and a rescoring of Cocteau’s BEAUTY AND THE BEAST with live singers crooning the dialogue, which had the effect of making me long to see the film with its original soundtrack).

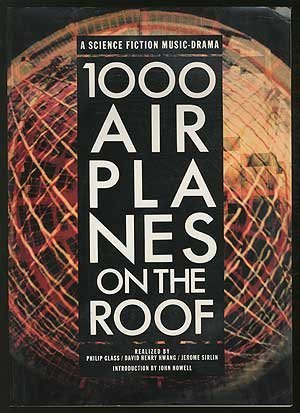

I know that, sadly, most of you will never have the chance to experience this innovative program in its intended form. Luckily a large format 1000 AIRPLANES ON THE ROOF paperback exists, published in 1989 by Peregrine Smith Books. Sumptuously designed, it contains the full text of David Henry Hwang’s script, accompanied by extensive still photographs taken from the July 1988 premiere of the show in Vienna, which picture actor Patrick O’Connell interacting with Jerome Sirlin’s holographic projections in a fair approximation of the order in which the events occurred in the live production.

What the book can’t capture, unfortunately, are the non-textual moments of music and image that for me constituted some of the show’s most memorable bits (meaning one should not use the book to critique 1000 AIRPLANES… without having seen the live production, a crime committed by at least one online critic). These include the aforementioned hopping-across-the-NYC-skyline sequence and a trippy mid-show montage of beehive imagery accompanied by an overpoweringly baroque music passage. So obviously the book isn’t the optimum version of 1000 AIRPLANES, but it is the closest thing to it right now.

memorable bits (meaning one should not use the book to critique 1000 AIRPLANES… without having seen the live production, a crime committed by at least one online critic). These include the aforementioned hopping-across-the-NYC-skyline sequence and a trippy mid-show montage of beehive imagery accompanied by an overpoweringly baroque music passage. So obviously the book isn’t the optimum version of 1000 AIRPLANES, but it is the closest thing to it right now.

And clearly, interest in this 25-year-old show remains constant. Check out two recently uploaded YouTube videos, which show that 1000 AIRPLANES has undergone some none-too-welcome mutations. The first video contains a clip from a performance by Scotland’s Red Note Ensemble that takes place in an airplane hanger, with the holographic design jettisoned. Even worse is a 69 minute video recording of a performance in an unidentified venue that replaces the Philip Glass score with a far blander one, and features primitive rear projected images of nondescript forests and buildings in place of Sirlin’s complex holographic montages.

My conclusion? That 1000 AIRPLANES ON THE ROOF is overdue for a revival, and one that includes the script, music and design that constituted the one-of-a-kind theatrical innovation it was and remains.